Featured Story • November 2015

The Coup in Elfland

Michael J. DeLuca

Before the firing squad, the King shed a tear. One marksman, poor, deluded paragon, the only one who still feared the forces that drive the gears of Fairyland sufficient to defy the “People”’s judgment, flung rifle aside and dived to catch that golden mote before it could strike the jadeite tile of His Highway. Then he was dead, speared with bullets like the King, all his holes sewn up with smoke. The other marksmen did as they were told. If a stray bullet shied, too many bullets had been fired that day, and everything was dizzy.

And the tear, the Tear of Elfland’s King—never mind why, whether for self or country it was shed, never mind whether the King, as the Three unseen mouths behind the conch-shell bullhorns of the “People” said, was a corrupt figurehead, the last anachronistic lie to mar the sensibly cacao-rouged complexion of Progress—the Tear pooled in the palm of that dead soldier and refused to dissipate despite the pressure of its peers the proverbial sweat on the brows of the multitude. There it remained, in the tropic March sun, drawing parrots to its sparkle, while the assembled hosts of Elfland dizzily made merry according to the Plan.

The Pompus came forth, his robetrain the breadth of the river, jesters, cowgirls, quetzals and capuchins cavorting in its wake. The bawdy patriotic song sprang from cupola and balustrade; the tankard was turned up, the cask staved. The bayonet rose and plummeted in the pattern of the wind-chased wave. And the new Clock in the Tower where the Three, those Inscrutable Three, conspired to conspire struck the same hour over and over, while the corpse of the King on the patio festered.

“How has it come to this?” said the Doggerel Poppet to the Popinjay, sipping oily-black espresso sludge in the sunlit window of the Once Café. “Where did the People steer our cornhusk-sewn catamaran awry? How could we allow the Iron here, the smaug? How did no one raise a cry? How did we welcome Death, that bloodied, lumpy-headed manatee, to pass the glam of our fair Fields? What did we stand to gain?”

“Change,” said the Popinjay, wreathed in the smoke of her clay calumet, tipping ash into a teacup, “my friend, Change.”

“It’s the end of an eerie, the turn of the tine,” pronounced the Pompus, gesticulating at the former Royal podium encrusted with the spores of clitocybes, “We must be revolute, we mustn’t stray,” while the loyalists marched before the guns to die; while the Three, the Ambiguous Three, remained sequestered in their spire; while the factory stacks dyed the nine skies of Elfland the seashell volcano colors of sand.

“What is to be done?” asked the mice, those sailors of the Fields.

“Is it enough?” asked the hobgobs, the wights.

“What seeds will spring, watered with such blood?” said the nahuals, the naguals, the spotted-cat knights.

“Why, old gods, dead immortals, why,” crooned the moribund corpse of the bullet-stuck Soldier, clutching the doughty droplet tight, “did I catch His Last Majesty’s Tear?”

When the marksmen had gone and the hobgobs, when the mice of the Fields lay drunk in the stubble, the crowds abed, and blithely the sweeps pushed shed carapaces from the streets, the dead soldier arose at his geas’s, his curse’s behest.

He was seen in the squares with the tatterdemalia, on the docks with the joblings, in the Fields with the mice, those corn-sailors, in the Café downing double-shots of aguardiente chased with chile piquín (the fire revived him, he claimed), brooding among corkscrew shelves at the “People”’s Royal stacks, or smudging his nose on the glass outside the abodes of the by-appointment-only. His rages were heard from the depths of the jar, his laments from the steps of the Tower.

“The King is dead, but not the Spirit. Elfland’s veins may be dug, split and funneled into export coffee trees to feed the sprees of foreigners, our rivers may be made to run with fume, the dust of Faerie quarried from the cliffs and lost to the air so that mortals downwind might fly off the handle. The Three, those Oblivious Three, tried to pull the heart of Faerie and replace it with the head. But the heart of Faerie won’t die with the land. It has survived the guns; it will outlast the iron and pass the factory smoke Changed but not rotten. Will it turn back to what it was? Not ever. But neither can it remain what it has become. We must rise! The people, the true People, must rise!”

Thus he nattered to all who would listen, displaying his token, the Tear of the King, to all who would see.

“Rise!” parrots echoed, “Fly!”

“How rise?” said the Jay to the Poppet, overhearing the echoes whilst strolling in the “People”‘s Royal Garden, recently renamed.

“How rise?” said the Poppet, nakedly brunching in bed with the Jay on popovers, chocolate and rum. “Who could stomach it? Are we not arisen once already? Are we not now the sorry savees of the Three?”

But the whispers spread, from the lips of parrots to the alleys where pale vermin dress as their ancestors’ ghosts and trade aniseed bread for corn-cakes wrapped in steam, to the docks where the spiderweb nets of the joblings unload the crystal fish to shatter, to the mice of the Fields, and at last unto the palace halls. When the Three, the Omniscient Three, had the word from the wights, in the drop of a pin they arranged for the soldier an intimate liaison with a murder squad.

In the Café they found him, the Tear in his cups. Said the Soldier as they pulled the triggers, and again as soon as ear-ringing allowed: “There is no more forever. Not in silence or in speech. Instead? The present. Besides, I am already dead.”

“What’s this?” said the sergeant-murderer, a comb-headed glum, peering one-eyed down his Iron.

“Here’s the problem,” said the coroner, formerly the cook, demonstrating with his thumb. “All the new bullets went through the old holes.”

So they carried his orating corpse to the palace patio; there the Pompus, hastily apprised, pronounced the most final of rites the most forcefully. Yet the Soldier, still squarely un-dead, said on. “From beyond the Fields this curse came, this geas. In the Tear of the King it may have congealed, but it did not enter his heart with the Iron, that slayer of eternity. No—for it came to the bullet from the hand, to the hand from the ear, to the ear from the mouth of the Pompus, to the mouth from the minds of the Three, the Heresical Three, and thence from among the very humblest of the People. Not only the cats and the alux, the wights, but the hobgobs and joblings and even the mice, they who walk the Fields, who reap and who sleep and who sail the swells of that fair fate-adjacent earth and hear its mumble. They feel the heartbeat of mortals, though they know it not! Beyond those Fields we know so well, the Mortal World now runs on grease and blood, and because this geas of Progress came thence, Elfland’s cogs must learn to turn on those selfsame commodities. In short, my People beloved, the Tear of our murdered king has shown me the answer to our pain: to save our land from this bastard fad, we must bring into our midst a Man!”

“A Man!” said the parrots, scattering this ghastly news to parrothued skies as the Soldier rambled and the Clock in the Tower went on failing to turn. “The mice!”

“A Man?” said the Doggerel Poppet, scribing foul verse on the subject of the Three in an egg-tempera of cinnabar and jobling blood on the wall of a fishmonger’s alley. “That never goes well.”

“There’s always a first time,” said the Popinjay, deep engaged in her crimson reflection in the pool around the jobling’s corpse. “Now there always will be.”

“Behead him!” squealed the Pompus, near upsetting his proud mitre of hibiscus-stained nagual-hide. “Extract his voicebox from its box, his brain from its pan, sow the latter in the green Fields with the corn and the former in the lava with the ashes of whatever’s left!”

Out came the axman with his ax (the gardener, formerly), the band played a fanfare of marimba, and he swung. The dead Soldier’s dust-dripping head was held high, finally silenced. Too late: his word had spread.

The Tear of the King rolled down between the headless soldier’s fingers, dangled forever as his body slumped, and then, when forever was over, plummeted into the waiting paw of a Mouse, who scampered between the sergeant’s legs and leapt into the claw of a Parrot.

“A Man!” cried the Mouse who carried the Tear, clinging to the Parrot’s leg as it soared over the Fields, over the rolling seas of smaug-stained corn, the ploughs now silent so recently belching, abandoned by mice who had given up sowing, taken arms, and gone into the city to Reap. The Tear of Elfland’s executed King flew on in the fist of the Mouse, his eyes alight with the fires of revolution, in the fist of the Parrot, giddily looping in the mad joy of the shiny, over the grease-surfaced river iridescing like a feathered serpent’s scales, over the other river of molten lava glowing red as a factory’s maw, and on, beyond the no-longer-forever, into the Mortal World.

The Mouse poured the Tear into the sleeping eye of the first Child in the first city he came upon, the only city insofar as he or Elfland cared, a tumbling, earth-shaken city whose rarefied air was choked with corn-smoke and the smaug of fire-colored buses packed with mortal men, where an orphan, urchin girl with black hair, without a bath or a brother, missing a toe and an ear, dozed on a cantina’s sun-tortured stoop, her fistful of pencils drooping, the other of coin clamped tight as a bum, dreaming by turns of war and of Faerie. When she woke and found herself crying a dread Tear not her own, a Parrot on one shoulder, the Mouse on the other whispering she was Elfland’s one true heir, she said, “Fuck, what took you so long?”

And she rose on her odd-numbered toes and carried them both to the edge of the city slum, where the pavements rotted away and the sharp-spined, severed-stumped forest begun. There, out of sight of mortal men, observed only by mortal birds, the parrot and mouse stretched to her meager stature or she shrank to their own and thus flew with them onward to Faeryland—she, who had been taught to dream since the war of a place without Death, she, its Heir.

In the years ‘twixt the moments since the King’s Tear had fled and returned, the mice of the Fields, those swillers of seed, had not idled. “Our Faery Queen!” they hailed her, tipping whiskers to the earth, when her lost toe touched the soil of the Fields so weed-grown though chemical-tainted. “Time is ripe for the plucking! The will of the ‘People’ is yours!” And they gave her the Thing they had made, two-handled and curving, tempered in lava, proofed in precious whiskey, forged not of Iron but of that which slayeth it, the Thing they called the Threshing-Blade.

“What the hell happened here?” the Heir whispered, beholding the ghosts and poisoned pyres that now were Faeryland. The Fields quaked with the volcano’s rumble and the Heir’s despair at her dream’s destruction, the Tear glistening molten in her eye. All the same, she took the blade. “Rust,” she named it, and it rode against her shoulder as she marched wobbling into the city, the mice at her heels swinging toothpicks and pins, flinging matches, twitching tails, screaming “Vengeance!” Parrots’ wings darked the nine skies of Elfland, blotting out all but the smaug.

Battle-conches were sounded, pink as tongues, from the palace walls. The joblings and the hobgobs trembled; the soldiers formed up in the squares. The ancestor ghosts in their pyramid tombs wailed, then quailed and were silent. The “People”’s Royal band struck up a death-dance on plywood guitars to the rhythm of the Clock striking seven again and again past the hour umpteenth. Cannon were raised to the summits of stelae; the canon was razed and replaced with mob rule. The Pompus left town for his villa, crossing the ford with forty to hold his robe from the sludge. The “People”’s King’s Highway, soon the Heir’s, filled with droves in dread of bad times come again, of “Resettlement” Camps and Disappearings, jadeite streets and temple steps slippery with smoke-scented blood.

“History repeats,” said the Poppet, with no small surprise, from under the bed, “just like the Clock. How can Time be so much like Eternity?”

“The Clock,” observed the Jay, from under the covers atop it, “only zigzags. It’s always Now—or else just about to be.”

“So much for Change,” said the Poppet.

“So much for escaping it.”

At this revelation, Poppet and Popinjay climbed from bed and from under it. The Poppet fetched cakes and coffee-press; the Jay flung windows wide. Wooden fingers twined feathers in lovers’ embrace; they broke their fast waiting for Elfland to burn, while the mouse host of the Heir, she herself at its head, advanced on the Tower of the Three.

“Let it end,” was her rallying cry, “Let it end!” for her lost ear heard remembered screams of grief and pain like no Faery had known because Real, and the mortal soil her lost toe had tread meant she alone in Elfland knew an end when she saw one. Rust bloomed wherever the Threshing-Blade touched; no Iron could withstand it. Engines fell; guns crumbled; factory stacks toppled like lumber; cannonballs were split in flight; phalanxes broke ranks and crept into alleys to cower.

At last the Three, the Solicitous Three, saw the way of the wind and came down from their Tower. Arrayed in invisible finery, soot-smudges and tattoos, they arranged themselves for genuflection mama-niña-abuela on the steps of the palace patio, where the King’s corpse had fallen and melted the stone, in the shade of the grand avocado that grew from the hole. No one bowed.

“You don’t understand, mortal Child,” said they, old, young and oldest, like the voices of a bellows-driven flue. “This had to be. Go away and come back when you’re older than trees, then you’ll know why we did what we did.”

“I don’t know what you did,” said the Heir, brushing black hair from her Tear-stained brown cheek over her absent ear. “I don’t care. I only know what has been done to me, how I lost what I loved, what I knew, and how I waited. All I want is what was promised. Eternity. But you took that away and left me this. So instead,” she said, hefting Rust, the Threshing-Blade, “instead, I’ll have an end.”

The parrots descended to perch on the smoking stocks of overheated guns, on severed limbs, haypoles, gambrels, sill and scrim, until the grand palace of Elfland resembled one cloud of myriad-colored factory smoke. “An end!” they said.

“It won’t work,” warned the Three, the Impervious Three. “Like the King, we cannot die, though Death herself, that saw-scarred manatee, once-emerald-feathered, were to sit in drab and tatters, toeless, on the very throne of Elfland. If you strike us down, it must begin again.”

“So what?” said the Heir, her blade dripping dust, the blurring, blinding, salt Tear of the King rolling endlessly out one eye, in the other. “That’s how it’s been in my world since before they died and left me. They told us that’s how it had to be. They told us to dream of this place. They told us that would make it better. And I did. And it didn’t. All I wanted was forever. I almost decided it didn’t exist. Now finally I’m here, and it’s gone.”

“Gone!” said the parrots.

“Gone,” snarled the mice.

The Heir spat in her hands. “Now I guess you’ll find out what that’s like.”

And with one blow, she took the Three’s heads.

The city celebrated, briefly; cask and tankard were already empty, the former People’s wealth, now the Heir’s, all but spent. The quetzals danced their stately dance to the tune of the reed pipe and drum. Haute hobgobs strolled the streets in slitted skirts, thighs paled with powder. The Jay and Poppet fucked against the windowsill, then passed the calumet pipe.

“Is it enough?” the mice asked, answered, “No,” and formed squads to stick toothpicks in the bellies of wights.

“What seeds will spring, watered with such blood?” said the nahuals, the naguals, the spotted cat knights.

The joblings said nothing, only piled into cornhusk-sewn catamarans on the molten harbor and set sail into the dark.

Death, the King’s Heir, had hardly sat crying an hour on Elfland’s throne before the Tower Clock again began to strike.

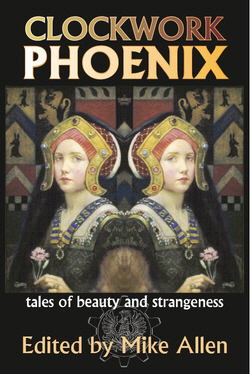

Michael J. DeLuca is the mushroom in this metaphor. His short fiction has appeared in Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Apex, Interfictions and Clockwork Phoenix. He guest-edited Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet #33, an ecologically themed issue that came out in July 2015. He narrates occasionally for the Beneath Ceaseless Skies fiction podcast, operates Weightless Books with Gavin J. Grant, and blogs at mossyskull.com.

Michael J. DeLuca is the mushroom in this metaphor. His short fiction has appeared in Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Apex, Interfictions and Clockwork Phoenix. He guest-edited Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet #33, an ecologically themed issue that came out in July 2015. He narrates occasionally for the Beneath Ceaseless Skies fiction podcast, operates Weightless Books with Gavin J. Grant, and blogs at mossyskull.com.

Michael tells us that “‘The Coup in Elfand’ has two pretty direct influences: one is Lord Dunsany; the other is Miguel Ángel Asturias, Guatemalan eco-surrealist reimaginer of Mayan myth and author of The Lord President, a novel about a Central American coup not unlike the one the CIA perpetrated on Guatemala in 1954, which led to his exile to Europe. I spent some time in Guatemala recently and fell in love with it; it’s a cradle of civilization in the Western Hemisphere and also ground zero for climate change; as they go, so go we. And I’ve been a fan of Asturias forever. To me, his life and his writing remain incredibly relevant, but nobody in the US seems to know about him. So I take every opportunity to bring him up—even when the story very probably speaks for itself.”

![]()

If you’ve enjoyed what you’ve read, please consider pitching in to keep us going. Your donation goes toward future content.

![]()