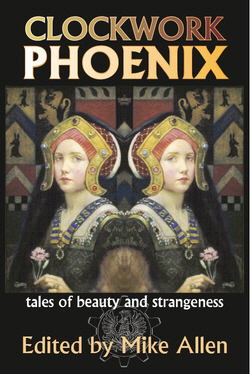

Featured Story • December 2015

Moon Story

Vanessa Fogg

Hush, little one. Calm down, little babe. You’re fed and dry and there’s nothing wrong, nothing will hurt you. See the moon outside your window? She’s peering in, and she’ll watch you even when I cannot. Let’s rock here in this chair, in this patch of moonlight. Let me tell you a story about the moon. Once there were two little girls who lived on the moon . . .

. . . And the moon was no dead airless rock, but a world of snow and ice, of frozen lakes and deep blue shadows. The sky overhead was always dark, but pierced through with countless stars. And fixed in the sky was a great planet, a luminous blue sphere shot through with shifting clouds of white.

The two little girls lived in a white tower on the moon. The tower rose alone from a high plateau, in the shadow of dark mountains. The children would stand on their tower roof and stretch out their arms and pretend they could reach the stars, or touch that great blue-and-white planet.

They were kept in that tower by an old woman with long grey hair. She called herself their mother, and why should they disbelieve her? Her matted hair trailed to the ground, and strange things crawled and slithered through the tangles. Beetles, and spiders, and rats with red eyes. Nameless things with pointed teeth. Black bats roosted there, and shy grey mice scampered through and hid themselves and stole stray tendrils to take for their nests. The little girls liked to explore the old woman’s hair, to part those rough curtains and feel for furry or scaly creatures. Sometimes they found old bones in her hair.

But the crone did not have much time for the girls. She spent much of her time in the tower’s library, muttering story-spells from heavy books, writing runes on paper soft as a child’s skin. Absently she stroked a rat that peeped out from her hair, and shooed the girls away when they came to her door. She would disappear for weeks on end, gathering rare herbs and jewels on the far side of the moon.

The girls were reared by Rat, a black rat that had grown to the size of a large dog. Rat it was who told them bedtime stories, and curled his body around them as they slept. His eyes were wise and glowed like flame.

It was not a bad life. Oh, not at all, little one! Did I say the old woman kept the girls in the tower? She did, but she let them out as well. When young, they were free to roam their world as they willed. All the world was their tower, their home.

Rat came with them on adventures, and the girls ran and leaped in the light lunar gravity. If you could see how high they jumped!

They dug tunnels through the snow, and sucked the pure water of moon icicles. They leaped off mountains. They tried to catch the white bats that flitted about the heights (a different breed from the black bats that nested in the old woman’s hair). When they were tired, Rat led them ride on his back.

Two little girls. Older and younger. A snowy moon-world as their playground, with each other as best friends.

I wonder if you can guess what happens next.

* * *

One day you will grow up, my little man. You’ll leave this house and go out to seek your fortune. You may travel far—to the ends of this world. And even that may not be enough. You may seek out new worlds, worlds I do not know, ones that I cannot see or touch or ever know.

Your story may not be dissimilar to the one I am telling now.

As the little girls grew, the voices of the planet above grew louder. They had heard these voices all their lives—faintly, in the mountains or when they stood at the top of their white tower. The noise was a meaningless hum, a sighing in the wind, something rarely noticed.

But it grew louder, and they began to notice.

The elder girl took to spending hours on the tower roof. Standing there, she thought that she could sometimes pick out individual notes among the tumult. Single words of unknown language. A sudden clear laugh or shout. And then the single voice would fade, lost again among the vast low roar.

“Listen,” she told her sister. The younger girl listened for a moment, and then, bored, ran off to find Rat for a game.

The older girl stood listening.

* * *

“Come with me,” the old woman said, and she took the girls on a journey to the far side of the moon. She showed them the dark-loving herbs she used in her spells, the white salamander that cannot abide the touch of the blue planet’s light, mountains larger than any they’d yet seen. From a rift in a mountain the witch pulled out jewels and dropped them into the children’s hands: each jewel the size of their own small palms, each the color of dark blood, glowing and pulsing faintly with the cooling fire of the moon’s core.

“Nothing up there,” the witch said disdainfully of the blue planet. “Noise. Mess. Trouble. Enough to see it from down here, where it’s just a pretty light. Or to come ‘round to this far side, where you can’t see it or hear it at all.”

“If you don’t like it,” the younger girl asked reasonably, “why did you build the tower on the side facing it?”

The old woman did not answer.

* * *

The younger girl began to listen the voices of the planet above. She took to wandering the mountains that reached closest to that other world’s light. In the chill lunar night, she heard the voices of other children across the void.

* * *

“See here, see this,” their mother crooned, and spilled more jewels into their hands; she gave them necklaces of pale moon-rock, shimmering like opals. She fashioned them delicate crowns of silver filigree: flowers and vines woven with bands of starlight. She who had ignored them through much of their childhood seemed now, fitfully, interested.

“Come here, see this,” she wheedled, commanded, and began teaching the girls, after her fashion, of old moon-spells and lore.

Occasionally, she spoke of the planet in their skies.

A horrible place, she said. So hot it will cook you alive. You’ll pop out of your skin from the heat, and sizzle like fat on the fire. The air of that place is so heavy it pulls you to the ground and wraps weights around your limbs; you’ll scarcely be able to lift your feet. Even for those born there—do you hear their voices in the night? Do they sound happy to you? Always crying and complaining. Oh, you would too, stuck amongst those crowds, stuck in that brutal misery.

The fire on the hearth hissed and popped as their mother spoke. The girls imagined sizzling in the heat of a far-off world.

And yet, they told one another, gazing out their tower window at that distant light—and yet how beautiful it looks.

* * *

As you grow older, my son, you will recognize a thread of this story in other tales. A call comes from another world. A voice summons the hero to a home he’s never seen. The horns of Efland blow—or perhaps he hears the song of a mermaid from the deep. To respond is dangerous. But to resist is to sicken and wither inside.

A blue star spoke to the younger girl, as she walked alone in the mountains. There is a door, the star whispered.

The older girl found a forgotten book in the library. Their mother thought she had hidden or burned all books on a certain theme, but there was one she had missed. The older sister flipped through the dusty tome, and paused at a picture of the shining planet called Earth.

There is a door, the star and book both said. A door in the mountains of the moon. A door to your heart’s desire.

* * *

Rat watched uneasily as the children made their preparations. They began by collecting Earthlight in crystal jars. Then they caught Earthlight in other vessels—moon-rocks, icicles, a silver ring. They harvested Earthlight from dewdrops in the warmer lowlands of the moon, and caught the sheen of Earthlight off a snowy bank. Rat watched them trap Earthlight in a pool of water, and then freeze Earth’s reflection in a mirror of ice.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“Just a game,” the older girl said lightly.

“An experiment,” the younger girl laughed. “Don’t tell Mother; it’s our secret.”

Later, Rat found the older girl building strange contraptions on the tower roof. Great shimmering bowls turned upward to the sky, mounted on blocks of stone. Pipes ran from the bottoms of the bowls into jars.

“What is this?” Rat asked, bewildered.

“Nothing,” the girl said. And then, relenting—“They catch sound. Listen.” She bent Rat’s ear to one of the pipes, and he heard the voices of Earth amplified.

“I’ll clean all this up before Mother comes back,” the girl promised. “Don’t tell.”

The younger sister broke apart her hoard of treasure. Crystals and fire-jewels, silver-stones and sapphires blue as Earth—she chipped and shattered them with a mallet she had fashioned from the black heart of a fallen star. She mixed the released light with the crushed powder of common stone and dust. “These are from your mother’s treasury,” Rat remarked as he nosed a string of emeralds. “Of course they’re not,” the girl said. She grinned. “Bring them here, she’ll never miss them.”

“No,” Rat protested as he followed the girls into the mountains. Obsessively they combed the same mountainside, circled the same mountain peak. “It’s no use, you’ll never find it,” Rat said. “It’s hidden away. You’ll never open the door; she sealed it behind her when she came.”

“What do you remember, Rat?” the older girl said fiercely. “Do you know where it is? Do you remember where you were—before?”

Rat shook his head. He had been so young—an ordinary rat, not even a witch’s familiar, a stowaway nibbling bread in her pack. He could not remember a time before he had come to the moon. Only the moment of stepping—falling—through.

“I am pledged to protect you,” he said with all the dignity a squeaky-voiced—though very large–rat can have.

* * *

Mothers see more than their children think. Even neglectful old witches.

* * *

The witch locked the girls in the tower. Of course she did. The outer doors vanished; save for the high windows, the outer walls became an unbroken surface. Only the witch passed in and out; how, no one could say.

Rat was not allowed in the tower to see the girls. The witch told him to keep watch from the outside, and he slept under their bedroom window. The girls looked forlornly down at him, long hair spilling around their faces. Rat swore that he had not betrayed them.

The sun rose and set; Earth stayed fixed in the sky, but swelled and then shrank to a sliver of ice-blue. “How long will you keep us here!” the children raged at their mother. And she—angry, heart-broken—raged back.

Until I know you will not leave, she answered. Until I know you will stay safe. Until I know the door is gone, and that you can never leave.

* * *

The sisters grew pale and thin. But they were still able to step out on the tower roof. They could still look at Earth, and listen to the voices calling them.

* * *

The girls escaped, of course. That’s part of the tale, too. They braided a long rope of hair. It was not their own hair they wove, but their mother’s. They bribed the little mice that lived in the tower, the mice that scampered through the witch’s hair and gathered strands to bring back to their nests. The girls bribed the mice with bits of jam tarts, with cake and cheese and left-over bites of their supper. The mice brought witch’s hair from their nests—the accumulation of years–and went to gather yet more. The sisters wove a magic rope: grey and weightless as smoke, yet stronger than steel.

On the eve of their escape, the girls were afraid. They had not been frightened through all their preparations: trapping Earthlight, breaking jewels—it had all felt like a game. But now they were afraid.

I did not tell you the girls’ names, my little one. Celeste and Selene. Celeste was the elder: quiet and thoughtful and intense. Selene the younger—laughing and daring and carefree. Yes, you know these names.

* * *

Earth was dark when Celeste and Selene escaped. No blue planet hung in the sky. Unseen in the night, the girls climbed down from their tower on a rope of witch’s hair. After, Celeste cut off a length of rope to take with them, but the remainder still hung tied to Selene’s bedpost.

Rat slept under their bedroom window, unaccountably tired. A sung lullaby, an enchanted breath blown from a window, a gift of cake laced with herbs pinched from a witch’s pantry–any or all of these might have explained it.

* * *

The children moved quickly through the night to their hidden cache in the mountains. Celeste lit the way with a jar of Earthlight.

Hours after their escape, Rat woke from troubled dreams. His nose and ears sensed the absence of human scent and sound. His red eyes—keener than the eyes of ordinary rats–saw the rope of hair swinging from the window.

Sometime after Rat had left, the witch herself stirred and cried out.

* * *

Rat knew the valley the girls sought. He knew their hidden cache.

But as he raced down the mountain ridge into that valley, he was surprised to see a brightness where none should be. Blue light spread over the surface of a frozen lake below. As he neared, he saw Earth reflected on the ice.

But it was the dark phase of the planet, and there was no Earth in the sky.

His steps slowed in wonder. The lake lit the entire valley. The Earth that shone from it was full and magnified, larger and brighter than it had ever been in the heavens. As he neared, Rat saw patches of green and brown on its surface; he saw white clouds swirling across its face.

There was something else as well.

A ladder stretched from the frozen Earth into the sky. A ladder bathed in Earthlight, but glimmering with its own light, too. A white and silver ladder that flickered along its length with glints of other colors—with sparks of flame, with reds and golds, with the green of emeralds and the shifting lights of opals. A ladder woven of the light of moon-stones and moon-jewels, light of the moon’s surface and ancient fire of the moon’s heart. A ladder shot through with Earthlight, bound together by the gathered songs of Earth, and threaded at the last moment with the grey of an old mother’s hair.

Two shadowy figures were climbing the ladder. They were only midway up, yet already high above. Rat watched the girls he loved; he watched them climbing up to a door he could not see, behind which surely lay the mirror image of the Earth reflected on the ice below.

Rat ran out onto the ice.

* * *

Amidst the hum of Earth’s voices, there came the flapping of great wings.

Rat had nearly reached the children. They had started climbing faster when they saw and felt him on the rungs, but he moved with the scampering agility of his kind, and needed only minutes to nearly close the gap. Yet he and they both stopped at the sound.

The witch had come, riding on a great black bat. Her hair streamed behind her. One hand stretched out, and she called her children’s names. Light flashed, and the three on the ladder saw her face.

The children wavered at the very threshold of the door.

Rat scampered up the final distance and pushed the children through.

* * *

As they fell, the girls had one last glimpse of her, she who they had called mother. And she was not the old grey crone they knew, but a shining figure of white. Her snow-white gown blew about her, and her luminous hair spread on the wind like a white river of light. Her silver eyes were lit with sorrow. She looked wordlessly at her children, and her sad face was ageless and beautiful, the face of the Lady of the Moon.

* * *

There now. There, my little bean. Your eyelashes flutter, and you sigh.

Your weight presses warm against me. Moonlight in this room. Peace and stillness, and the rhythm of your breath.

I regret none of it, my little one; I regret nothing. I am not sorry that I came to this place of heat and noise, where gravity pulls at my limbs and the beat of my heart. I am not sorry that I came to this crowded world, where even the air feels heavy in my lungs, and the moon in the sky is but a dead, airless rock. I cannot regret it, for I have you . . . And I have your father in the next room as well.

And I still have my sister, although we no longer share a bedroom, or even live in the same city.

Hear the scratch at the door? It’s your friend: Rat is crossing the room. We have him again for a while. Celeste’s place in the city was too small for him, and her condo board doesn’t allow dogs anyway. Especially not dogs that look disturbingly like large black rats. There’s only so much a glamour-spell—our very last—could do.

Rat’s curled here at our feet, and the Lady Moon outside your window. Your eyes are finally closed. Do you know how beautiful you look? How perfect you are—the curve of your round cheeks, the way your lashes lie long and dark against those cheeks. The perfection of your rosebud mouth. Of every tiny sigh and breath.

You’re fast asleep. I should lay you down and go to sleep myself.

But I’ll hold you a just little longer. I’ll hold you while I still can. Because soon you will be taking your first steps away from me. Soon you’ll be going out into that great wide world. And the human world is more vast and strange than I’d ever dreamed. My mother tried to keep me safe from it. My human Earth-mother, who in a distant age begged another to care for and protect the children she could not keep. My shining moon-mother, who agreed.

But Celeste and I know this truth: that the world cannot be shut out, nor the heart’s desires denied. Though your feet may stay Earth-bound, still you may stray farther than I can follow. There are worlds within worlds, and I cannot tell which ones you’ll seek and reach. Which ones will crush and which ones will let you fly. I can only pray for your safety. And I can only hope that years from the moment that you first walk away, you’ll retrace your steps and come back to visit. I can only hope that, unlike me, you’ll find a way to return.

Vanessa Fogg writes of dragons, cyborgs, and other oddities from her home in western Michigan. She spent years as a research scientist in molecular cell biology and now works as a freelance medical and science writer. Her fiction has appeared in a variety of places, including GigaNotoSaurus, Lakeside Circus, The Future Fire, and LabLit. She is a believer in the Oxford comma. To learn more, visit her website at www.vanessafogg.com.

Vanessa Fogg writes of dragons, cyborgs, and other oddities from her home in western Michigan. She spent years as a research scientist in molecular cell biology and now works as a freelance medical and science writer. Her fiction has appeared in a variety of places, including GigaNotoSaurus, Lakeside Circus, The Future Fire, and LabLit. She is a believer in the Oxford comma. To learn more, visit her website at www.vanessafogg.com.

Vanessa tells us that “‘Moon Story’ started as a tale to entertain my daughters on a long airplane flight. There wasn’t much of a plot to it, initially; it was just the adventures of two little girls on the moon, skipping and leaping about with their great black Rat. But the story kept at me; over time, a plot slowly took shape and the images poured in. I was influenced by William Joyce’s lovely picture book, The Man in the Moon, which I read to my youngest. My first nephew had been recently born, so one of his nicknames sneaks into this story, too. My girls are eight and ten now, but I clearly remember holding them in the night, just as the mother in this story holds her son.”

![]()

If you’ve enjoyed what you’ve read, please consider pitching in to keep us going. Your donation goes toward future content.

![]()