Featured Story • September 2013

Echoes in the Dark

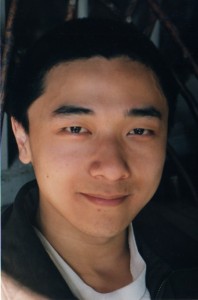

Ken Liu

A True and Correct Account

of the Adventures of Captain John James Carrington

in the Chinese Empire

To welcome me to Shanghai, the American Consul General hosted a banquet in my honor.

The Chinese waiters streamed to and fro, bringing an endless array of foods exotic and strange to me: roasted duck dipped in rice wine, chilled longan fruit shaped like eyes, shrimp carved to resemble lutes. They worked efficiently and quietly, their Oriental faces impassive and inscrutable.

As we dined, I sought information on the leader of the rebels, a man nicknamed the Soaring Bat.

“The Chinese speak of him as a great fighter,” my cousin said, “skilled in the ancient arts of combat. They call him by the honorific Ta Tsia, which I’m told means ‘Great Hero.’ Many are the tales of his prowess in battle and generosity towards the poor and helpless.”

My cousin, a water engineer with the International Settlement, had invited me to Shanghai to advise them on security preparations. There was talk of a plot afoot by a group of Chinese fanatics, remnants of the Taiping Rebellion, to poison the water supply of the various treaty ports to discourage the expansion of foreign enclaves in China, which the rebels viewed as an outrage. The American residents of Shanghai did not trust that the incompetent and craven mandarins of the Ch’ing Court would properly protect the International Settlement.

“Oh, he is but a mirage,” said another man, the owner of a steamship line. “The Chinese exaggerate this phantasm to assuage their foolish pride. Even if he exists, he is surely like his countrymen, a feeble opium addict who will crumple at the first demonstration of Western arms.”

“Shanghai is a small haven in a populous and vast land,” I said. “It behooves us to be respectful of our opponents.”

I was used to men like him, men who thought fighting a game. But I had seen too much bloodshed at Shiloh and Gettysburg. After the conclusion of the Great Rebellion in 1865, I had sought to lay down the sword for the plow and find solace in my apple orchard outside Providence, Rhode Island. But here I was, a few years later, my revolver and sword by my side, far from home. In the eyes of the world, sometimes a soldier is always a soldier.

The man laughed. “The Chinese are a declining race, destined to fade from the stage of history. Have you forgotten that Commander Frederick Townsend Ward was able to defeat the Taiping hordes and protect Shanghai with only a ragtag team of a hundred deserters, discharged seamen, and drifters? Treat your time here as a holiday, Captain, for there is no threat.”

I resolved to learn more about the facts before forming an opinion.

* * *

During the next few days, I traveled around Shanghai to study her defenses and evaluate the security of her water supplies.

The city lived up to her tawdry reputation. Every street corner seemed to hold a storytelling pavilion, where singsong girls performed their t’antz’u to slovenly and lascivious crowds. Servile and sickly men emerged from the opium dens behind bamboo fences.

But what made the greatest impression on me was a walk down Fourth Avenue at sunset, as the streets were filled with young Chinese women full of the most bold coquetry and seductive gestures, so that I thought even the most stalwart man would have been tempted.

I wondered if the man at my welcome banquet had been right about this decadent and indolent land.

* * *

About a week after my arrival, I went on a survey of the rural countryside around Shanghai to scout for possible alternate sources of water that could be secured in the event of a rebel assault.

While on a stretch of road between two villages, my wagon suddenly stopped because a herd of pigs blocked the road. As my porters went up to shoo them away, masked men jumped out of the tall grass by the side of the road and surrounded us.

The cowardly porters immediately abandoned me and ran away. I managed to get off two shots with my revolver and might have wounded one of the bandits, but the others overwhelmed me and made me their prisoner.

The bandits blindfolded me and brought me on a long trek uphill.

Eventually, I was tied to a chair and my blindfold removed. But it might as well have been kept on, for I found myself in almost complete darkness.

“I’m sorry for the way you were invited here.” A voice spoke out of the darkness. The man’s accent was heavy, but he spoke slowly and softly and I easily understood him. “Some of my men are servants at the American Consulate. They speak highly of you as a man with an open mind.”

Though startled, I strove to remain calm. “Who are you?”

“My name is Ts’ai Ch’iang-Kuo, the last of the Taiping commanders. I was born sightless, and I’ve learned that it is better to try to converse with the sighted in darkness. It seems to make you more willing to listen. The Ch’ing generals call me the Soaring Bat to mock me, but I’ve grown to like it.”

Now that I had some time to orient myself in the darkness, I saw that I was in a small room, barely ten feet from wall to wall. A bit of light from a lamp in the next room leaked in under the door, and I could hear the sounds of men shuffling playing cards on the other side.

I could just make out by the faint light the figure of a tall man sitting on the bed across from my chair, his legs crossed under him. His hair, I saw, was long and worn loose, not in a queue, and his forehead was not shaven as was the custom in China. I vaguely recalled hearing that this meant he refused to submit to the Manchu Emperor.

“Whatever you’re planning,” I said, “it will not work. Shanghai is well armed and whether you like it or not, we own Shanghai and we’re not leaving.”

My interlocutor sighed. “Captain Carrington, we have no quarrel with you or your people. The rumors you hear of my ill intentions are spread by the Ch’ing mandarins.”

“What?”

“You must know that the Heavenly Kingdom of Taiping is a Christian rebellion. I myself studied with an American missionary as a child and learned much to admire about your people.”

I had heard that that the Taiping did purport to be a strange sect of Christians. “Yet your commanders threatened to run all foreigners into the sea.”

“I cannot speak for all the Taiping forces. But our goal was to overthrow the Ch’ing. China is a country under occupation, Captain. The Manchu Emperor and his noblemen believe that this land is their private garden, and the people of China are their slaves. Think, Captain, what kind of ruler would rather slaughter his subjects than defend their lives against foreign gunboats? Until we put an end to this dynasty, the Chinese will not have justice or freedom.”

His goals were ones I could sympathize with, if true. “Why have you kidnapped me then?”

“The Ch’ing Court manipulates France, Britain, and the United States to help solidify its rule against China’s people. Perhaps your governments prefer to support it in exchange for favors and profitable concessions. But that is shortsighted. I brought you here to ask a favor of you.”

But before my captor could say more, a lone, loud whistle rang out in the silence of the night, like a bird soaring into the sky, followed by a loud explosion.

“Signal rockets,” my captor said. “The Ch’ing forces have surrounded us. They’re eager to prevent you from hearing what I have to say. No matter. Come with me.”

* * *

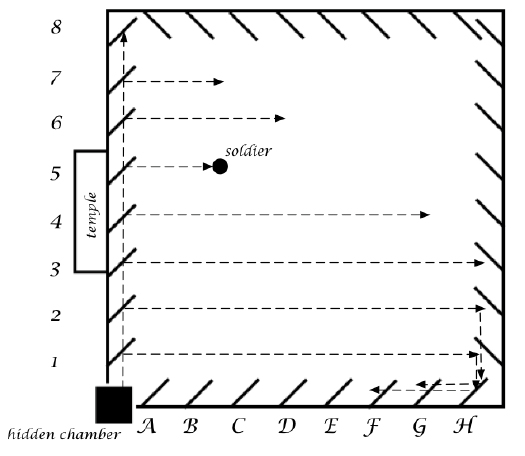

The fortress was built within the ruins of an old Buddhist temple carved into a cave at the foot of steep cliffs. In front of the cave was a large walled courtyard roughly square in shape.

Ts’ai and I crouched within a small chamber at the southwestern corner of the courtyard. Through a crack in the walls I was able to see the scene outside.

Torchlight revealed about a hundred Ch’ing soldiers with muskets and spears approaching the courtyard, the flickering light glinting from their weapons.

To mount an assault on the temple, the attackers must first scale the walls of the courtyard and cross the empty space. Logically, I would have expected the rebels to defend themselves by manning the walls.

But the walls were empty.

Ts’ai leaned over and whispered in my ear, “This is an old trick I learned from the peerless Chuge Liang, Prime Advisor to the Han centuries ago. The appearance of an undefended city will lead them to suspect a planned ambush. With their torches, they’ll be easy targets. So they’ll choose to fight blind, like me.”

Indeed, within moments, I could hear the Ch’ing commander giving urgent orders in hushed tones, and the torches were quickly extinguished. It was a night of the new moon and overcast. All was now inky darkness.

I nodded, impressed with my host’s tactical acumen. Without firing a single shot, he had induced a measure of anxiety into the enemy and caused them to voluntarily give up one of their advantages. He might not have gone to West Point, but he would have done well as a Union commander during the Great Rebellion.

But I still didn’t understand his plan for victory. During our rush to hide in this chamber, I noted only about two dozen rebels inside the compound, and no muskets. It also stood to reason that the government forces would be better-equipped and disciplined. Even in complete darkness, it still seemed that the odds were against Ts’ai.

Indeed, I could hear ladders being propped against walls, and the muffled sounds of men climbing up and jumping down. A few minutes later, I guessed that the bulk of the Ch’ing forces were now inside the courtyard. Although there must have been more than eighty men in the courtyard, they were extraordinarily quiet, and there was no way to tell where exactly they were.

Then Ts’ai did something that I shall never forget. He began to hum.

It was halfway between a song and a moan, deeply resonant. Sometimes he seemed to be saying “om” and other times he seemed to be saying “nam.” I could feel the sound vibrating in the walls around me, and I could hear it echoing in the silent night air.

He would hum for a few seconds, stop, and cock his ear to intently listen. Then he would change the pattern of his humming, altering pitch, duration, rhythm. It sounded like the description a New Bedford whaleman once gave me of the singing of the great fish.

I began to hear other sounds as well, the sound of men screaming in death. At first the sounds came singly, seriatim. But soon the screams merged into each other, rose to a crescendo, and I could feel the fear, the panic, the despair in the pleadings for mercy against unseen enemies in the night.

The fading sound of a horse’s hoofs told me that the Ch’ing commander had abandoned his men and left. The screams of the dying gradually quieted, and all was again darkness and silence.

I let out an explosive breath that I had not realized I was holding. I was just about to speak to Ts’ai when the wooden door to the stone chamber flew open and a Ch’ing soldier stumbled inside, brandishing his spear.

A few arrows stuck out his back, and blood flowed freely from his wounds. As he careened around the room, I pressed myself against the wall and felt hot drops of blood splattering onto me. His movements were powerful but chaotic, the last throes of a dying man.

My host was completely still and quiet. Crouching in the dark, he was no doubt hoping to strike a fatal blow against the wounded soldier without being impaled on his frenzied spear first.

Now, this was my chance to turn the tables on my captor. I could assist the Ch’ing soldier, subdue the Soaring Bat, and claim a reward from the Chinese government as well as the gratitude of the International Settlement.

But I remembered Ts’ai’s words, and I realized that I liked him. A soldier knows when to trust his instincts.

I lunged forward and twisted the spear out of the soldier’s grasp. Using it like a bayonet, I ended his life with one quick thrust.

“Thank you,” Ts’ai said.

* * *

In the light of the morning, as Ts’ai enjoyed the warm sunlight on a stone stool and sipped his tea, I carefully examined the courtyard and tried to reconstruct what had happened.

Here, I have with me a rough sketch I drew of the place. It is the same sketch that I later used in my application for a letter patent filed after I returned to America.

The angled baffles against the walls were made of hard and smooth slabs of stone. As I clapped my hands before it I could hear the crisp way the sound rebounded from it.

“These were constructed using the same material as the famed Echo Wall at the Temple of Heaven in Peking,” Ts’ai said. “Sound does not die against it, but rather bounces off cleanly.”

I gently touched the walls, cold and polished, not understanding.

Smiling with his sunken eyelids shut, my host continued. “Blindness gives me an advantage. My school of martial art has had many blind masters in its past. They refined the art of night fighting, where one uses ears to substitute for eyes. These stones and their use were passed down to me from these ancient masters.”

When Ts’ai was humming last night, he had directed his sound to travel along the western wall, such that the sound would be deflected by each of the baffles along the indicated path in my diagram. A single sound was thus split into eight echoes, each of which crossed the courtyard along a latitudinal line. At the eastern wall the echoes were deflected again into a southerly direction until the baffles along the southern wall sent them back towards Ts’ai in the corner room.

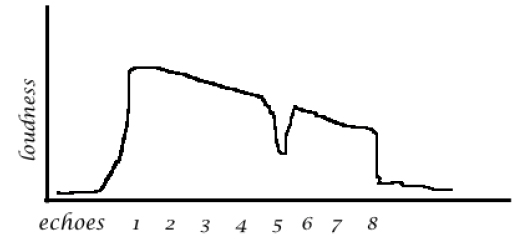

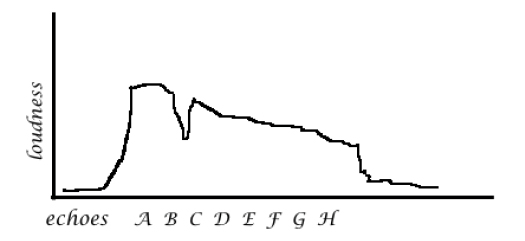

Since each of the echoes traveled a different distance before arriving back at the chamber in which we hid, they accumulated together in Ts’ai’s ear as a long, gradually diminishing echo.

“It sounds like the string on a kuch’in slowly returning to rest.”

However, when something was in the courtyard (for example, a Ch’ing soldier), one of the eight echoes would be absorbed at the obstruction’s location, resulting in a slight dip in the expected sound. If I map out the amplitude of sound over time, it would look something like this:

“You can tell when the dip in sound occurs?”

Ts’ai smiled proudly. He stood tall, the sun on his face, his back as straight as a pine tree. “It’s a simple trick. All that is required is practice, concentration, and the ability to focus chi.”

Similarly, Ts’ai’s humming also was deflected at the northwestern corner to travel along the northern wall, where it was again deflected into eight separate echoes traversing the courtyard from north to south. If an obstacle in the courtyard intercepted one of these echoes, there would also be a slight dip in the expected sound.

Together, the eight echoes going east-west and the eight echoes going north-south divided the courtyard into a grid of sixty-four squares. Based on when the dips in the returning long echo occurred, Ts’ai could use his ears to “see” where enemy soldiers were. For instance, in my drawings, he would see that a soldier was standing at the square marked by the coordinates B and 5.

If other soldiers stood elsewhere in the courtyard, there would be more dips in the echoes he heard. But of course Ts’ai did not use coordinates like mine.

“The sixty-four positions are named after the sixty-four hexagrams of the I Ching. My followers and I use a code so that by altering the patterns in my humming, I can call out each of the squares. Last night, my men hid inside the temple and concentrated their arrows in the darkness at where I told them the Ch’ing troops were. They shot without having to aim, using me as their eyes. And that was how we won.”

* * *

Ts’ai’s favor turned out to be a request for me to act as an emissary to the International Settlement, and to the governments of Britain, France, and the United States.

“Soldier to solider, I ask you to persuade them to stop supporting the Ch’ing. Surely you see they’re unworthy of the support of Christian nations.”

I explained to him that in my experience, governments, even Christian ones, tended to favor winners. After all, Britain was willing to support the slave states of the Confederacy until she saw that the Union’s victory was inevitable. If he wished for Western nations to stop propping up the Manchus, then the Chinese would have to show that they were capable of winning freedom on their own. It was a harsh lesson, but in my view, necessary.

He cocked his head, and smiled. “You believe that we must claim what we want by our own strength of arms.”

“Yes.”

“Even if that means someday we may ask your people to leave Shanghai and return it to us.”

I considered this, and reluctantly agreed. “Such is the way of the world.”

“Thank you,” he said. “You’re indeed a man of honor.”

“I should be thanking you.”

He asked what I meant.

I shared with him my excitement at learning the secret of his method of sightless detection. I could already see how this technique of seeing by sounds and echoes could be improved by science and apply to numerous arts in both war and peace.

Bringing to bear the principles of the phonautograph, which I had heard described by an acquaintance who had visited Édouard-Léon Scott in France, I thought it possible to transform the echoes into visible traces on paper, thus allowing an untrained man to match the skill of a master martial artist’s ears. As well, using the motive force of electricity and ingenious mechanical clockwork, I could imagine automatic actions to be triggered upon the detection of an object.

My mind raced with possibilities. I had seen the first underwater warships deployed during the War for which no practical means of detection existed. But with this system of sound pulses installed near a harbor or shipping lanes, subsurface boats could be “seen” without sight. Also, banks and vaults would pay dearly for a system that could detect the presence of intruders and would-be robbers in complete darkness. And these were just scratching the surface.

As I described these visions to Ts’ai, his face went through a series of emotions: amusement, wonder, fear, then resignation.

“What is the matter? Master Ts’ai?”

“I am struck by the difference between our civilizations. My teachers and I have studied and passed on this ancient technique for generations as a means to compensate for a personal weakness. But you saw something I never could: an invention that would be useful to many more by the addition of mechanical engines to magnify human forces and senses.”

“This is the age of invention,” I said. “All nations’ fates depend on it.”

He became silent and thoughtful. At length he said, “My ancestors were once a people full of invention, too.” He paused, and then added, “Perhaps we will be again, someday.”

Together, in silence, we contemplated the fickle fortunes of nations and civilizations, the easy seduction of manifest destiny and providence, and the wandering paths taken by Man in the search for freedom and progress, like the echoing paths of a sound in the darkness.

Author’s Notes: The acoustic-wave technology described here is actually based on a real sensing technique, as disclosed by US Patent #4,644,100, “Surface Acoustic Wave Touch Panel System,” invented by Michael C. Brenner and James J. Fitzgibbon, issued on February 17, 1987. The diagrams in this story are based on the drawings found in the patent.

Ken Liu is an author and translator of speculative fiction, as well as a lawyer and programmer. His fiction has appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Asimov’s, Analog, Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, and Strange Horizons, among other places. He has won a Nebula, a Hugo, a World Fantasy Award, and a Science Fiction & Fantasy Translation Award, and been nominated for the Sturgeon and the Locus Awards. He lives with his family near Boston, Massachusetts.

Ken Liu is an author and translator of speculative fiction, as well as a lawyer and programmer. His fiction has appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Asimov’s, Analog, Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, and Strange Horizons, among other places. He has won a Nebula, a Hugo, a World Fantasy Award, and a Science Fiction & Fantasy Translation Award, and been nominated for the Sturgeon and the Locus Awards. He lives with his family near Boston, Massachusetts.

About “Echoes in the Dark,” he says, “for my day job, I do a lot of work with patents, and it’s fun to imagine steampunk versions of the same inventions. This story came out of one of those daydreams.”

![]()

If you’ve enjoyed what you’ve read, please consider pitching in to keep us going. Your donation goes toward future content.

![]()