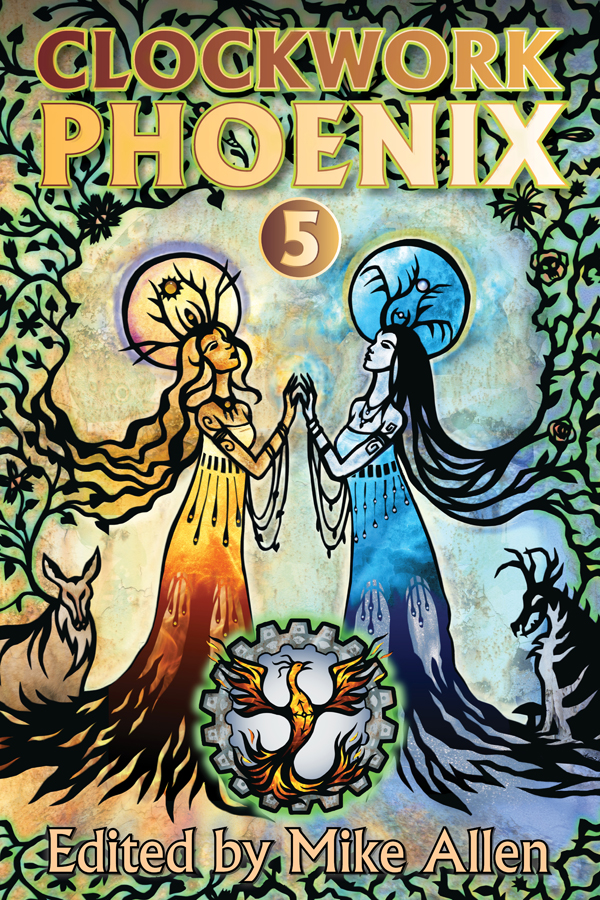

A Clockwork Phoenix featured story

Squeeze

Rob Cameron

Gone: two stolen “I messed with Texas” shot glasses, photos of us at your niece’s graduation, seashells you found in the middle of that parking lot in Great Neck, my empty Red Hot Chili Peppers CD cases, your panties under my bed. High on grief after your funeral, I took everything imbued with your essence and shattered it against the wall or burned it like witches at the stake while the smoke detector screeched in short bursts.

I stopped speaking to people. In the morning I would dress myself, chin to chest, fumbling with buttons, head bowed like the lilies on your casket, and take the 7 train from Times Square to where you used to live in that ancient duplex on the corner of Cherry Avenue in Flushing, last stop. That’s where we had chilled on your landlord’s bleached porch swing with our feet up, drinking Red Stag whiskey in every kind of weather. That’s where, in your own quiet way, you had tried to prepare me for the inevitable.

Since you weren’t there anymore, there was no reason to get off the train. So I’d wait for it to fill with bodies and ferry me back to Manhattan. Unable to move forward or go back, this became my life for maybe a hundred years (time moves differently on the 7). Passing under the lethean waters of the East River eroded my memory until I couldn’t remember your face or the smell of your hair. Terrified, I listened for your voice, but it was lost in the dull roar of rush hour.

* * *

One morning, as the train emerged at Vernon Boulevard in Queens, a stinging sensation struck the crown of my head, forcing my starving mind to aggressively adhere to the smallest, most perfect details which, while still of no interest to me, now could not be ignored.

At Queensboro Plaza, light traveled broken paths through the scratched, stained window and became prismatic, oscillating streamers of blue, purple, and gold. Bruised tangerines scattered through space like cooling stars born from the bursting scarlet plastic bag of an elderly Chinese couple at Roosevelt, bloodying the air with their tart flavor. Squat graffitied rooftops were a fast-moving dream coming into focus while neck muscles tensed against the subtle pull of gravity as the train came to a full and complete stop at Junction Boulevard.

The platform was crowded. Plump Ecuadorian children played soccer as their parents pressed shoulder to moist shoulder for position by my train car door, weighed down by toddlers, baby carriages, and carts. The doors shushed open and all of Queens flooded in, eager to escape the sharp briars of a New York summer. Everyone had an unhealthy metallic sheen to them, beaded with mini vernal pools. The sudden influx of heat and mass made my teeth ache with stomach-turning vertigo. As my vision doubled, a little ghost boy slipped under the turnstile and appeared on the train.

The doors chimed, shushed together, and we moved. The MTA kept the cars cold enough to retard the ammonia-producing chemistry of so many bodies. The chilled spot I heard you’re supposed to feel around poltergeists didn’t even register.

The ghost child blinked in and out of existence. Every time he reappeared, I had to remember him all over again, like catching the tail of a fleeing dream. At first I would be watching a square of light crinkle and color like tinfoil as it drifted through the car. Then a child would cry, and the light became the boy, going through people’s bags or sitting on old women’s laps.

He pulled the pacifiers from beautiful sleeping brown babies and tried to lift them from their seats. He finger-painted messages from the dead into the grime on the window. Sometimes he used his face. He danced around the pole singing at the top of his lungs, which sounded like the screech of the train wheels going around a turn at incautious speed.

It’s easier to imagine the ghosts of men than “ghost children.” The two words in juxtaposition cry out for a comma between them or a period, a division of ideas in the same way there should be a barrier between life and death. That lack of imagination is why people don’t see him.

In the same way, it is difficult for a young child to understand death. So sometimes they do not die.

Although calling it a child might be misleading. The ghost looked right at me, one eye glaring white, while the other was a hole, impossibly deep. But I was not afraid.

I wondered why I could see him when nobody else could. Then I remembered near-death experiences can shift your perspective. Losing you had almost killed me.

The ghost child climbed up next to some woman, knelt backward on the bench, and looked out the window while babbling. The woman had one arm. The other was gone at the elbow. I’d noticed her in the same way I noticed anyone on the subway. There was a process: awareness, speculation, judgment, and ignorance.

Awareness: She was tall and brittle, skin made of a dark, distinctly nonnative graphite; her eyes were chips of tarnished bronze. I could tell she’d been more colorful once. Recent fossils show dinosaurs had feathers. There were imprints in the stone. Feathers meant color. She was like that—imprinted.

Speculation: I imagined her homeland was once a happy place where everyone sang everything everywhere they went. It was Eden, it was Zamunda, it was The Lion King, but with Real People. Then disaster struck. She’d escaped on a boat that was over capacity. It tipped, and she swam to shore through the floating bodies of loved ones and strangers. She’d survived and now rode my 7 train to the last stop.

Judgment: I didn’t like her because she would take up two seats; because she wasn’t big enough or crazy enough to deserve two seats; because I looked at her and thought, Bomber. “Nigeria is experiencing a rash—a rash!—of female bombers,” said some CNN breaking news update somewhere.

Because she wasn’t you.

Ignorance: After a while, she became background, and my eyes passed over her, flattening her like the ads for 1-800 immigrant legal services I didn’t need, surgical body hacks I couldn’t afford, and postcard-sized notes stuck in the seams of the subway maps, warning of a wrathful second coming of Jesus I didn’t believe in.

I’m sure everybody noticed me in the same way.

All of a sudden, the woman slid over and made room for the ghost child. He turned, sat, and took her hand, or where her ghost limb would have been. She squeezed her other fist, but you could imagine.

A small sound escaped from both her and my opened lips, and her body, which had been a desert, briefly flooded with color. She looked through me, eyes glistening with tears that welled but did not fall, and before I could blink them away, my vision blurred, too.

I realized we had been on the same commute now for years. She’d been squeezing her fist just like this every evening at exactly this time between Junction and Flushing. Of course she’d always been able see him. I wondered what else she had lost along with her arm. I wondered what else she could see. Maybe it was a trick of my peripheral vision, but for a moment she and the ghost child shared an unmistakable resemblance.

I suddenly found that I’d walked through the crowded train and was standing in front of her.

“I see him, too,” I said.

“The boy?” she asked, her voice carving out each syllable with precision.

“I thought I was the only one,” we said at the same time.

“Is he your son?”

I could tell she wanted to say yes. “I don’t know what he is.”

We stood together in awkward silence, neither of us used to talking, while the train pulled into Flushing and emptied.

“This is my stop,” she said, walking past me. Then she turned back at the door. “How sad is it that we need the dead to connect to the living?” Which is something you would have said.

The ghost boy was gone, too, and I sat alone in my train car.

But then it began to fill back up with people. Tomorrow we will talk again. If not tomorrow, then the next day. It will be another great adventure, like loving you, which was the same as facing death.

Rob Cameron is an ESL teacher in Brooklyn. When he’s not writing stories, planning events for the Brooklyn Speculative Fiction Writers, or producing the Kaleidocast, he finds time to climb large objects, race dragon boats, fight ninjas, and pity fools. His e-mail address is cpr.words@gmail.com, and he blogs at http://rob-cameron.com.

Rob Cameron is an ESL teacher in Brooklyn. When he’s not writing stories, planning events for the Brooklyn Speculative Fiction Writers, or producing the Kaleidocast, he finds time to climb large objects, race dragon boats, fight ninjas, and pity fools. His e-mail address is cpr.words@gmail.com, and he blogs at http://rob-cameron.com.

Cameron tells us he wrote “Squeeze” while road-tripping from New York City to Burlington, Massachusetts, on the way to Readercon.

Click here to see the list of Kickstarter backers who made Clockwork Phoenix 5 possible.

Order from: Paperback: Amazon | Amazon UK | Amazon CA | Amazon DE | Barnes & Noble | Indiebound

|

“Allen’s strange and lovely fifth genre-melding fantasy anthology selects 20 new short stories of unusual variety, texture, compassion, and perception. . . . All the stories afford thought-provoking glimpses into alternative realities that linger, sparking unconventional thoughts, long after they are first encountered.” —Publishers Weekly, starred review |