Featured Story • September 2017

Sunrise with Sea Monsters

David Sandner

Margate, 1833

Mr. R– first saw the madwoman on a cliffside overlooking the sea, waiting for sea monsters. The sun had not yet risen. Fog embraced the cliffs as night receded like the tide revealing shining sand. Cold touched the back of his neck, his cheeks, his nose, his fingers, anywhere his coat left uncovered, but the woman wore only a thin white dress, plain and ill-made, and a ragged shawl tight about her shoulders. He did not know then she was mad. Perhaps the thin dress should have been his first clue? He was startled to meet anyone at the lonely spot where he had come to paint the sunrise. She struck him as beautiful, her raven hair spread across her back and against the white fog, but forlorn so that his heart ached.

Awkwardly, knowing he should, as the intruder on her solitude, speak first, perhaps even offer his coat, he instead, to have something to do, began to set up his traveling easel. She turned her face to him, neither surprised nor aware of him before she heard him. Unearthly, he thought, which pleased him. He felt abashed to have disturbed her . . . yet peevish to find someone blocking a view he had carefully chosen at a time he expected the cliffside to be empty.

“Sorry,” he said, loud over the waves churning below. “I thought no one would be here.”

She gave a ghostly stare, brown eyes glinting as if tears welled.

“I’m a painter, working en plein air, to do the sunrise, you know.” He motioned out, taking in the world, his canvas, but she only stared. “It’s beautiful here,” he finished lamely.

She would prove, he could tell, immune to hints. The fog continued to brighten and to lift, making visible more and more restless water below the bluff. Soon the sun, and then the light he had come to paint, would be past. He tried to think what to say next but she spoke first.

“I’m waiting for sea monsters,” she said.

* * *

“When I was eight, my father beat my mother with a stick big around as his thumb. That’s legal size, he told her, for a husband to use on his wife—as if that made it the very type he should use to beat her. He drank to excess. Gin. Often to blindness. He frequented some of the worst gin palaces. He worked steadily nevertheless—in fact, he was . . . is successful. In the Law. But never happy. Prone to melancholy. He would come home nearly blind, ready to pass out in his clothes, usually. But other times, violent. He had beat her many times. But this time, a stick. He called her terrible things and rushed her in the kitchen. The servants fled, dropping their work. The crack of the stick on flesh made me wince. I watched, hands to my face. He was worked up fierce, the beating without end. I cried silently. Finally, she seemed to not have the energy to lift her arms to fend his blows. He seemed only more infuriated. I thought she would die. She no longer called at the blows but cried in a strangely mechanical way, like a stream train stuttering down. He no longer heaped invective, but grunted with each blow. He would not stop. I leapt. Sudden. From whimpering, I came wild. I bit him and scratched and tore and yowled. He threw me into the wall. I fell, broken, to the floor. He turned and raised the stick when my mother—she leapt now biting, scratching, beating. He pushed her back. She grabbed a cleaver the servants had dropped. She brandished it, grunting like a cornered beast. He fled. I thought he would return to kill us. But he did not. He beat her again when drunk but . . . he never used the stick again. He seemed strangely scared of me after.”

She spoke her remarkable soliloquy while looking out into the ocean, where sea monsters dwell. Finishing, she turned to Mr. R–, her face a study of concern.

“I did good, yes, in the world, then?” she asked him. He struggled to reply but nothing occurred to him to say.

“I did this. It did some good—the beatings were never as bad again. No stick. I did something good?”

It was a child’s questions, a child’s insistence.

She had said all this perhaps five minutes into conversation, after introductions and nothing more.

“My name is Mr. R–,” he had said. “The painter?”

He hoped to be recognized, perhaps, for he had some fame, but she betrayed nothing.

“I am Mrs. Grave,” she said simply and he found her name apt. She turned back to her monster watch. With no further preamble, she revealed the monster who had reared her.

She stared at him now, awaiting reply.

“Yes,” he said. “I’m sure you did her good.”

He began to think she meant to throw herself into the sea, like a modern-day bride for the Kraken. They continued awhile in silence but for the wind whipping the sea.

“I must get back,” she said, finally, with a sigh. “Time is short.” She turned away from the indifferent waves. “I will return tomorrow,” she said to him.

“As will I,” he said.

As she stepped away toward higher ground, he said, “but what of the sea monsters?”

“Not today,” she said. “Tomorrow perhaps.”

He sketched the sunrise in his book, feeling the integration of shape and design in the movement of things. Turning to his easel, he tested colors directly on the paper, smearing careful mixes of red and yellow—always more yellow!—trying to capture light on paper. He quickly made the sky with a palette knife, then turned to a small brush for the untamed sea. It was a good day’s work, done before midday. He left in good spirits. He saw no monsters at all in the open sea.

* * *

“May I paint you?” he asked, when next they met.

She briefly made a vinegar face.

“You’ve learned I’m . . . mad,” she said simply.

“I learned you lived on the hill . . . .” He gestured vaguely.

“I could see it in your eyes.”

He stared into hers and felt perfectly foolish.

“Yes,” he said.

She waited.

“My mother—I helped place her in Bethel,” he said. He willed himself not to turn away, not to look down. “But she raved, Mrs. Grave. She excoriated us as devils; she spoke to angels.”

“And I,” she said, “to sea monsters, is that it?”

He nodded.

“Yes, I suppose,” he said.

“Thank you for your directness. My husband placed me in Penthem House—the house on the hill. I am not mad. My father helped him. My mother died when I was thirteen—a dear uncle of hers died two years later and I came into money, five hundred a year. Not my father—me. My mother had confided in my uncle, and he had written stringent requirements on the will for my protection. Oh, that he had not, I might be free! But I was a foolish thing. I liked fashion and dance, the whirl and the color. A beautiful young man turned my head. I married him, and not a month passed before he told me he hated me. He and my father wrote out legal documents denouncing my sanity—and I am but a married woman, sir, and have no standing to contradict my husband. To the law, I would be contradicting myself, my own being. Removing me here, they seized on my money—for my own good, the courts said. I will see that money no more.”

She gazed out to sea. He thought on her story. As on the day before, the sun was still a promise beyond the horizon. The sea smelled bitter and salty, with a sweet hint of decay.

“I, too,” he said, “like the whirl and the color.”

They sat in silence on the rocks, windblown, watching the clouds stretch thin or stack into hayricks in the sky. The sea snapped with whitecaps as its waters rocked to deep unseen forces.

“I must go,” she said, pushing up, hands on knees.

“Before your keepers notice you’re gone?”

She nodded.

“But I don’t understand about the sea monsters—how do they come into this?”

“You mean you don’t believe me.”

“How can I?” he said.

“Seeing is believing?” she said. It was a question.

“What? Oh, no—you’re right there.” He thought of fierce arguments he had had in well-appointed salons with useless popinjays who posed as real painters. “What we see is illusion—we are corrupted by what pleases us or what repels.”

He shook his head violently.

“I don’t know what I mean by disbelieving you! I just find it difficult to . . .”

She turned away.

“What does a sea monster look like?” he asked, with a kind of despair.

“How should I know?” she said. “I shall return tomorrow.”

“So shall I,” he said.

* * *

He never approached the house on the hill, for fear of revealing Mrs. Graves’ morning escapes. He sketched and painted all mornings, then drank his afternoons away, brooding on her.

“How do you always get her before me,” he asked her one morning.

“My walk is shorter.”

“Why do you wait for sea monsters,” he said. “That’s what I don’t understand.”

“I called them to come.”

“Dear God, why?”

“There is nothing for me here,” she said sharply. “I am a woman—to be such a thing is to be half-mad by nature—not quite man.”

“You could escape—I would take you away!”

“You checked on me, yes—my story.”

It wasn’t really a question.

“Well, I asked about you, too—about the man I could see from my high window—the stranger with the easel to go painting at Widows’ End.”

The bluff was called that for wives were said to stand watching—some forever—for their men returning from the sea.

“I hear you have taken up with a widow yourself, old Gurdie who lives by the landing?”

He nodded. He was not a young man. He had known both the wife and her husband before the man died. The seaman had died naturally in his bed some five years previously. Mr. R– had visited to paint the area ten years ago, renting a room from the seaman and his wife; returning, he had looked up his acquaintances and found only the widow, and had “taken up” with her . . . not as discreetly as he had supposed . . . as well as renting a room.

“Will you marry her?”

He reddened. He was not a young man.

As she rose to go, he said, “But what will happen when they come?”

“Perhaps nothing. Or perhaps I will be free. I only call them. I do not control them.”

He asked her again if he could paint her, but she would never answer that question.

At night, he dreamed, turning restlessly, of her falling into open jaws.

* * *

“But how do you call the sea monsters?” he asked her. “What do you mean? What will happen? Will they take you to a land under the water?”

She laughed, for the first time. He laughed in surprise.

“What a lovely thought. No.”

He stared at her for a long time.

“Will they devour you?” he finally asked. He had visions of her eventually leaping to her death to “meet” the sea monsters.

“Oh—no!—how horrid! No.”

“Then what is the point?”

“Let me ask you this, Mr. R– . . . your painting here. Can you walk in it—enter some other world?”

“No.”

“Will it destroy you? Devour you? Is it not just a painting?”

He heard the echoes of many arguments at many a salon.

“It is, indeed, just a painting,” he said quietly.

“Then why paint it?”

She asked for the truth: though he knew many sorts of half-answers, spoken—by himself!—at many of those salons, he gave her the only truth he knew.

“It’s a mystery.”

“It is mystery.”

She surprised him.

“Precisely so,” he said.

They sat in silence until she had to leave. Then he painted with renewed vigor. He used his thumb to smear the waves into spray, ghostly dancers spinning into thin air.

* * *

Again and again, he returned to the cliffs, to her. She did not always come—which drove him half-mad. He came but to see her. Since he could not paint her, he began to paint everything else and yet somehow he would paint about her, where she would be, how she made him feel. He could not explain. He felt he painted now only to pass the time before she came to the cliffside, or to fill her extraordinary silences.

One morning everything was different. She was not there, and so he feared that meant it was a day when she could not get away. But there was something in the air, in the quality of light.

The wind was the song. It beguiled him; he held his breath and turned his head to listen closer. It was not in the wind. The Old North Wind blew song over the wild sea.

The waves broke in fierce harmony.

He wouldn’t breath. His heart sounded its rhythm, his blood churning loudly in his ears. Finally, he exhaled yet still the sound did not diminish. It did not break up into wind and wave but endured, impossibly.

A strange whistling broke through the song and all other sound, weaving under and above everything and then pulling it tight.

She had come up behind him without his knowing it.

“They’ve come,” she said, her hand on his shoulder as she spoke directly in his ear to be heard above the weird keening.

The sea monsters sang a fairy song.

He broke into a sweat and felt momentarily blinded as the blood churned in him again.

“I hear,” he said, gaping.

He took a step forward, away from her hand on his shoulder.

He felt he had to leap, to be with them. It is a siren song, he thought, but could not stop.

“Lash me to the mast,” he shouted.

But there was no mast. No crew, only a madwoman to detain him. He stepped to the edge of the land. He regarded the wild sea then as an emblem of his soul. He let one foot dangle over the abyss like a possibility. He stepped on the wind.

He fell, ecstatic, into the sea of wind-song and wave-song and the coiling of creatures who embraced the world at creation’s heart. They drew him down to the foundations and crushed him into blackness.

* * *

Yet he awoke, or seemed to.

He found himself in bed—not his bed. A storm blew, rain tapping arrhythmically on a window.

He tried to rise and was gently held back by a hand on his chest. He sought to assure the women who attended him—one young, one old—that he was fine. He realized, somewhat dimly, his mind set on the cliffside, that they were nurses and determined to tell them what they wanted to hear. They thought he had fainted. He did not care how he came to be there. He complained that he had not eaten enough, being but a foolish painter; he had pressed himself too hard to finish a work—but he had learned his lesson. His traveling easel sat in a corner, still a bit damp. He could not have been here long. He did not attend to the room, or the women or the doctor they brought to see him. Mr. R– smiled and joked, and assured, and made light, and admonished his own foolishness most piteously. He did not ask about the madwoman. He certainly did not ask about sea monsters. (Their coils clenched his heart still!) He rose slowly. He showed easy movements. He did not hurry. Against his better judgment, the young doctor released him. Mr. R– shook the doctor’s hand, yet he would not have recognized the doctor’s face again in the street.

His heart lived the song, fierce and all-consuming.

He nearly forgot his easel—a dead giveaway!—in his hurry to leave (at a slow pace). He made a joke about absentminded artists. He walked out into the rain, tasting the water on his lips in gladness. The doctor’s office abutted the asylum, was connected to it somehow—not that he cared . . . he was not far from the bluff.

He ran down to the sea—to his desire. Had he not leapt in? How had he not leapt in? He had leapt! It was nearly night, low clouds scudding over the sky, but he could see her silhouetted at land’s edge. He knew she would be there. Others would be looking for her, surely. One way or another, she had escaped for the last time. She turned and strode toward him. In her eyes, a sadness, resolute and all hers alone. It frightened him.

He heard the wind wind-up its tune; the waves began to beat the shore in time; a whistling built as two shapes appeared from the horizon, coiling in the whitecaps and rain and darkness falling.

Mr. R– moved toward the overlook but she caught him and kissed him and he knew not if it was day or night. For a moment, she was with him. Only for a moment, they were but a man and a woman embracing on a cliffside overlook in the dark of an approaching storm.

All sound ceased but her heart and his own. She drew back and looked into his face. She had eyes wide as the sea.

“You’ve saved me.”

“I save myself,” she said.

“I do not hear them.”

Something had loosened in his chest. He felt relief, but bereft.

“They come for me,” she said. “You cannot go. Not yet.”

“I would take you away . . . ”

He was crying, but could not feel it for the rain.

“There is no place for me here. But other worlds interpenetrate our own. Perhaps I will come back. But not to you. Do not wait. This is not for you.”

She closed his eyes with her fingertips and he retreated from consciousness with a sigh.

* * *

He awoke, sheepish, to the ministrations of the two women—one old with a strict conscientiousness, while the other, younger, was careless but kind. They made a good pair, he came to decide. The doctor was very young, sleepless, and did not meddle too deep in his patients’ reasons for falling ill—a kindness, indeed. Still, they kept him a week, feeding him broth and spooning him tonics. The widow Gurdie came and snuck him bits of jerky and sometimes a pint flask to pass the time.

Finally, when he pleaded he must go home, must leave Margate and return to his home north of London, they released him.

He did not return to the bluff.

Or to see if the poor, wronged madwoman was back at the asylum.

He was as certain she could no longer be found at either spot as he was in the power of silence and the profound dark at the bottom of the sea.

He took a ship to London. The rocking did not make him seasick as when he had come. The sea, then the river Thames, lay calm, mostly. Seagulls glided on warming winds. He stood by the rail, staring down, speaking to no one.

At home, he finished his painting of the sunrise by consulting his sketches and his memory. When he displayed the work at Exhibition, he arrived on Varnishing Day—his last chance for finishing touches—to add detail. In the lower left, he conjured two uncertain sea monsters, eyes wide and strange, looking out the waves. Who would believe in them? Let them wonder, he thought, of his audience. Let them lean in and stare. And if they can, let them feel—let them remember—the coils around the heart.

He had painted her, finally, he felt.

He knew the perfect title for the painting.

David Sandner is a member of the HWA and SFWA. His work has appeared in leading magazines, anthologies, journals, websites, podcasts, and radical zines. He is a professor of English at Cal State Fullerton. He has written and edited books on the history and origins of the fantastic and its genres, including Mythopoeic Award finalist Critical Discourses of the Fantastic, 1712–1831. He recently chaired the 2016 Philip K. Dick Conference and curated the Philip K. Dick in the OC, a website on Philip K. Dick in Orange County, CA. He is working on an edited collection, Philip K. Dick, Here and Now, and on a site called The Frankenstein Meme, exploring the influence of Mary Shelley’s novel. He can be found at davidsandner.com.

David Sandner is a member of the HWA and SFWA. His work has appeared in leading magazines, anthologies, journals, websites, podcasts, and radical zines. He is a professor of English at Cal State Fullerton. He has written and edited books on the history and origins of the fantastic and its genres, including Mythopoeic Award finalist Critical Discourses of the Fantastic, 1712–1831. He recently chaired the 2016 Philip K. Dick Conference and curated the Philip K. Dick in the OC, a website on Philip K. Dick in Orange County, CA. He is working on an edited collection, Philip K. Dick, Here and Now, and on a site called The Frankenstein Meme, exploring the influence of Mary Shelley’s novel. He can be found at davidsandner.com.

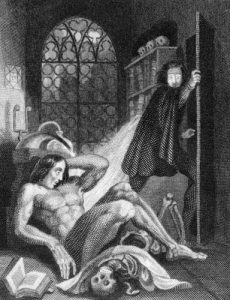

He shared that “Sunrise with Sea Monsters” is “based on a painting of that title by J.M.W. Turner. It does indeed have some uncertain sea monsters in the waves. It’s a strange work; I loved the title, and it got me thinking.”

![]()

If you’ve enjoyed what you’ve read, please consider pitching in to keep us going. Your donation goes toward future content.

![]()