Featured Story • October 2017

The Elevator Illimitable

James Van Pelt

“Going up, sir?” said Lamar, his blue pillbox hat with gold piping at exactly the right, jaunty angle. A heavyset business man, wearing an unbuttoned jacket and loosened tie stepped aboard.

“Seventh floor, please.”

Lamar slid the outer door and inner gate closed in two practiced motions.

“Hard day, sir?” He rotated the elevator lever to the left. Distant machinery hummed to life—Lamar felt it in the control—before the elevator lurched upward. Floors scrolled past, their numbers visible through the gate. He pulled the crank back to the upright position, stopping the car exactly level with the floor. It wouldn’t do to have a passenger step up or down to exit, even if it was only an inch. “Perhaps a before-dinner martini would be in order, sir. You’ve spoken of your love of poetry. This could be an evening for reading and contemplation.”

The businessman nodded. “You are right, Lamar. Wordsworth and libation. Good call.” He reached in his pocket. “I don’t know how you do this job. Ten-by-ten room all day. It would drive me crazy.” He shook the elevator operator’s hand, leaving a folded one-dollar bill before he stepped off.

Miss Hattem, waiting for the elevator on the first floor, held a cat carrier in one hand and a briefcase in the other. “Sub-basement four, Lamar.” Brown hair cut short, tanned face and an athletic build, she wore a red and grey flannel shirt with the sleeves rolled to her elbows and new blue jeans. If Indiana Jones had been born as a woman, he might carry himself the way Miss Hattem did.

Lamar closed the doors, moved the lever to the right to send the lift down, then stood at attention at his station. “Ma’am,” he said, “whatever you’re carrying doesn’t like you.” A milky-colored, clawed hand reached out from the cage, swiping at Miss Hattem’s leg. The claws were more like needles than bone. She slapped the cage with her briefcase, eliciting an angry squeal from the occupant.

“That might have stung,” she said.

Lamar bent low. “May I?”

“Don’t get close. By ‘stung’ I meant, all my blood clotting instantly with painful death to follow.”

One large eye stared out from a baby-skin pink, bald fist of a head. Arms that ended in tiny human-looking hands, all equipped with needle-adorned fingers, sprouted behind it like a mutant spider.

“Where did you get him?”

“Around: a place a couple blocks from here where people don’t look.”

“I’ll stay away from the spot.”

“How will you know?” She smiled wryly.

Lamar stood, brought the elevator to a smooth halt and opened the gate. No ceiling lights illuminated the hallway beyond, but lit signs above the doors provided a soft, blue glow. Two men pushing a large dolly loaded with a wooden crate walked by. Something growled within.

Miss Hattem said, “It’s always busier down here during the change of the season.”

“Don’t I know it,” said Lamar.

Back at the lobby level, two muscular women supporting a bloodied man who looked dead boarded next. “Seventy-second floor,” said one. Before the doors closed, a raven flew in and alighted on one of the women’s shoulder.

The women wore long, wool skirts, leather boots, and broad belts with long, straight unsheathed swords thrust through iron loops. Their shirts were also wool, drawn closed with leather string, and both covered blonde hair with metal, winged helmets.

The man’s shirt was rent in both the chest and back.

“Sorry about your carpet,” said one. Blood dripped steadily.

Lamar said, “How’s your friend?”

“He’s a hero,” said the other, regripping the man’s arm.

On the seventy-second floor, sounds of revelry and music flooded the elevator. The women walked out with the man’s feet dragging, but before they were ten feet away, he seemed to recover, straightened, and joined the party. Lamar couldn’t see the room’s opposite wall beyond the long tables and crowd dressed like his passengers, but he smelled cooking meat and heady mead.

Paper towels soaked up most of the blood. Still, Lamar wrote a memo to housekeeping to steam the carpet.

Johnny Kamdar, a ten-year old who lived on the eighteenth, got on next, his book bag under his arm. He smiled at Lamar. “I think I can stump you today.”

Lamar activated the lift mechanism. “Give me your best.”

“What’s on the sixth floor of Macy’s?”

“The Herald Square store?”

Johnny laughed. “Is there any other?”

“Good point. Hosiery, lingerie, and home/textiles. Also a Starbucks, a candy shop and a couple restaurants.”

“Dang, I was sure I’d get you on that one. How about this, what is the tallest building in Dubai, and how many floors is it?”

“The Burj Khalifi, with 163 floors.”

“How far off the ground is the Sky Deck in the Sear’s Tower?”

“1,353 feet.”

“Ok, how about this? When the Empire State Building was hit by a B-25 in 1945, what floors were impacted?” Johnny looked smug.

“The 78th to the 80th. They couldn’t find the body of the pilot for two days because he’d punched through an elevator wall and plunged to the bottom. Also, an elevator operator named Betty Lou Oliver was hurt in the crash. She was on the 80th floor when the plane hit. A bunch of debris fell through the top of her car, fracturing her neck and back. After they stabilized her, they put her on another elevator to go to the hospital, but that one’s cables had been weakened in the crash. They broke, and she fell for 75 floors to the basement. She survived!”

Johnny glanced at the elevator’s roof, as if he expected to hear breaking cables. “Bad day for Betty Lou Oliver.”

“She’s a legend among operators.” Lamar stopped the car and pulled the gate and door open. “Here you are.”

Johnny turned around after leaving the car. “Is there anything about buildings you don’t know?”

Lamar thought about this for a second. “Undoubtedly. New buildings go up every day. Old ones come down. Facts abound.”

He picked up the next passenger on the thirty-fourth floor. “Sub-basement fifty,” the tall, slender, impeccably dressed man said. He positioned himself in the car’s center, hands clasped behind his back. They didn’t speak for many floors as the numbers slid past.

Finally, Lamar said, “That’s a long way down, sir.”

“Indeed.” The man studied Lamar, who suddenly felt exposed. He said, “Are you happy with your lot in life, Lamar?”

Lamar had a very good memory for names and faces, but nothing about the passenger seemed familiar. “Very, sir.”

“I suppose you would be. You are a poor man’s Charon, a transporter of people, a noble profession. Still, a man may find a time when he wants to strike a deal.”

Lamar stopped the elevator. Opened the inner gate and then the outer door, which was distinctly warm.

“If you find someday that you really, really want something, come down to see me. I’m sure we can come to terms.”

“It seems unlikely.” The car smelled distinctly of brimstone.

The man shrugged, then strode out.

Three preschoolers, a girl and two boys, boarded with their nanny on the ground floor. “Twelve, please,” said the harried-looking woman.

“You are outnumbered, ma’am.” Lamar started the car.

“It’s stinky in here,” said the little girl.

“Like matches,” said one of the boys.

“Like rotten eggs,” said the other.

“Children, be polite.” Dark circles under the nanny’s eyes and worry lines around her mouth made her appear older than the university sweatshirt and psychology 101 textbook under her arm indicated.

“When I grow up, I want to run an elevator,” said the little girl. “Can I pull the lever?”

“I’m sorry,” said Lamar. “Only the operator can handle the controls. Safety regulations.”

She looked disappointed.

“I want to have adventures,” said one of the boys. “The elevator man doesn’t have adventures. He just goes up and down.”

The nanny shushed the boy and looked apologetically at Lamar. “Little kids don’t have filters.” She addressed the children. “Everybody has job, and every job has a body.”

“Well said, ma’am.”

The next passenger wore a spacesuit and helmet that muffled his voice, but Lamar knew the high floor he wanted where a gray, cratered, starlit plane waited. Then a businessman got off at the bank, and a nurse got off at the morgue as a pallid man in a hospital gown boarded. He never spoke and faded away before Lamar opened the doors again. A woman wearing flip-flops, a bikini, and sousaphone exited on the fifth floor, while a Boston terrier trotted into the car. Lamar checked the hallway outside, but wherever the sousaphone player went, she’d already got there because the hallway was empty and the doors were closed.

The dog got off on the ground floor.

His next passenger hesitated at the door. An old man, bent and tottering, his hand shook as he rubbed it against his cheek.

“What floor, sir?”

The man didn’t react at first, and then he flinched, as if he hadn’t noticed Lamar standing there. “Are you Taylor?” He squinted at Lamar.

“I don’t know Taylor. I am the elevator operator.”

“I thought you were Taylor, my brother, Lieutenant Taylor. He lent me his car so I could take Cindy to the dance. She said we were humdingers in uniform. Are you sure you’re not Taylor? Oh, that Cindy could dance. Quite a kisser too.” He spoke with pauses, silent interruptions. He stepped into the car, and then backed out. “Your living room needs a couch.”

“Are you lost, sir? Were you going someplace?”

The man moved into the car, painfully. Breathing seemed hard. “Here’s the thing,” he said, “I never know where I am. Nothing’s familiar. That’s a pisser.”

Understanding dawned on Lamar. He should have seen it earlier. “I can take you home, sir. Hold on. We’re moving.”

Lamar engaged the gear as gently as he could so that the elevator barely lurched.

“I’ve been walking forever,” said the old man, more to himself than to Lamar.

When the doors opened, a man wearing a military jacket festooned with pips and medallions and an army dress hat, the American eagle clutching a feather and arrows in its claws above the brim, was waiting. Beside him stood a lithe blonde woman in a yellow dress with a huge bow at the neck. In the background, a jazz group played.

“It’s the Lindy Hop,” the woman said, putting her hand out.

“We’ve saved you a seat near the band,” said the soldier.

Lamar stood aside so the old man could make his way, and after he closed the doors, the elevator operator wiped tears off his face.

Hour after hour, Lamar opened the gate and the door, greeted passengers, closed them in, then rotated the crank. People rose or descended. The spoke or were silent. Some tipped. He was unfailingly polite and attentive. Every ride surprised him in some way. People always surprised him.

Young Johnny Kamdar smiled broadly when the elevator door opened on the ground floor. “Hi, Lamar.” He almost skipped into the car, his book bag slung across his back.

“Do you have a building question for me?” Lamar drew the door and gate shut.

“How many floors does this building have?” Johnny waited, smiling.

The elevator rose without a click or tremor. Somewhere, high above—how high?—the machinery drew it up. A counterweight sank. Someone standing outside the doors might hear it pass. If they pressed the call button, it would eventually come for them. Every stop was different. Who knew what waited?

“I can’t tell you, Johnny. I truly can’t. We call them floors, but that’s not the only name for them.”

“What do you mean?”

“A tall structure is made up of stories. This building has too many stories to count.”

“How come a floor is called a story?”

Lamar brought the elevator to a stop. “Just because it is, sir.” He straightened himself, wearing his working clothes with pride. “Things are what they are.”

Johnny waved as he left.

On the next stop, three male elves boarded, tall, long-haired; a brunette, blond, and redhead, carrying bows and wearing leather quivers. An intimidating trio. Their pointed ears poked prominently.

Lamar thought, what is their story?

The brunette, whose hair fell to his waist, must have sensed the unasked question. He stuck out his hand. “Jackson Pryor. Our accounting firm is having a masquerade on the twenty-first floor. This is Raymond, vice-president in charge of new accounts, and Teddy, our second-year intern.”

“Of course, sirs. Well met. I am Lamar.” He closed the gate. “Twenty-first floor it is.”

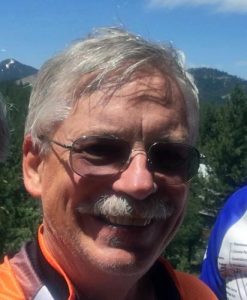

James Van Pelt is a part-time high school English teacher and full-time writer in western Colorado. He’s been a finalist for a Nebula Award and been reprinted in many year’s-best collections. His first young-adult novel, Pandora’s Gun, was released from Fairwood Press in August 2015. His next collection, The Experience Arcade and Other Stories, will be released at the World Fantasy Convention in 2017 (and maybe for MileHi!). James blogs at http://www.jamesvanpelt.com, and he can be found on Facebook.

James Van Pelt is a part-time high school English teacher and full-time writer in western Colorado. He’s been a finalist for a Nebula Award and been reprinted in many year’s-best collections. His first young-adult novel, Pandora’s Gun, was released from Fairwood Press in August 2015. His next collection, The Experience Arcade and Other Stories, will be released at the World Fantasy Convention in 2017 (and maybe for MileHi!). James blogs at http://www.jamesvanpelt.com, and he can be found on Facebook.

About the writing of this story, he shared, “I’ve always liked the idea of an elevator operator. It looks like it should be a dull job, but if you were a people person, it would be an opportunity to make snapshot contacts with humanity. Over time, as the same people ride the elevator, a complete portrait of each might emerge. That kind of thinking lead me to write ‘The Elevator Illimitable.’”

![]()

If you’ve enjoyed what you’ve read, please consider pitching in to keep us going. Your donation goes toward future content.

![]()