From the pages of Dark Breakers

Salissay’s Laundries

C. S. E. Cooney

Illustration by Brett Massé

for Sally Tibbetts

Seven Days in Hell, i.e., the Seafall City Laundries. Falling to the Depths. Walking with the Wretched. Finding Wonders on the Way.

by Salissay Dimaguiba

Table of Contents

-

Introduction. In Which My Boss Prepares Me for a Mission Requiring Intrepidity, Cunning, and a Powerful Disguise

-

Chapter i. In Which My Disguise as a Wretched One of Seafall Proves Unnervingly Efficacious

-

Chapter ii. In Which I Describe the Seafall City Laundries, Disparage a Mattress, and Meet a Friend.

-

Chapter iii. In Which I Am Placed with the Washers, Go Snooping—and Get Caught!

-

Chapter iv. In Which I Meet the abbess of Ironwood Institution, and She Surprises Me

-

Chapter v. In Which My Situation Takes a Grave Turn—Possibly Literally!

-

Chapter vi. In Which, in the Dark of the Wells, I See Strange Writing and Learn Terrible Things

-

Chapter vii. In Which I Ascend and Learn the Secret of the Salt Cellar

-

Conclusion. The Aftermath

Introduction. In Which My Boss Prepares Me for a Mission Requiring Intrepidity, Cunning, and a Powerful Disguise

When my editor at the Courier called me into her office and told me it was at last time to enact the final—and most dangerous—part of our investigation into the Seafall City Laundries, I grabbed my checkered coat from the back of my chair and buttoned it all the way to the throat. In days of old, when going into battle, knights errant reportedly had silver helms and brazen greaves and probably some sort of enchanted shield. I, alas, have only my checkered coat, with its shoulder cape and worn velvet cuffs. It covers me neck to toe and is by now a decade and a half out of fashion, but when I am wearing it, I feel the most like myself: the bravest, the most competent, and the least visible—which are exactly the three traits that serve me best in my work.

I also knew that after today, I might never see my beloved coat again. Tomorrow, when going undercover to investigate the rumors of gross abuse, neglect, and misuse of resources at the Seafall City Laundries, I would have to leave it behind, along with my identity. Few who went through those gates ever came out again, and I was not counting on being one of them. Hoping for, yes. Planning for, yes. Counting on, no.

“How’s my ace reporter?” asked my boss, indicating the chair in front of her desk. Her expression was particularly sardonic at the moment—as much an indication of her nerves as was my coat, buttoned to the chin on such a balmy afternoon.

I did not sit. Not on the chair, anyway. I perched at the edge of her desk, like usual, and answered lightly, “She’s ready to expose a bunch of oldfangled gentryphobes for the exploitative hypocrites they are, boss. And then she’ll retire young—well, young-ish—let’s say, respectably middle-aged—and eat bonbons the rest of her life, living off the fame and fortune this exposé will garner her.”

“Like all those other exposés did, Sal?”

“Hey, I made out okay. I own my apartment outright, at least.” I let the flippancy fall. “So. Tomorrow then?”

My boss adjusted her spectacles. “Yes. Mazzi phoned in to say her cover’s been cracked. One of the Archabbot’s chaplains found her snooping and reported her. Narrowly escaped a few goons from the Abbatial Gendarmerie. I wired her some funds, so she’ll be hopping the next Night Bullet across the water and should be back in Seafall soon. We’ll have her lie low a while. I’ve secured a safe house,” her face went grim, “and I’m hoping it’s safe enough. Meanwhile, I’ve sent replies to all the letters—even the oldest ones, though we’re probably too late to do any good in those cases. There’s always a chance, you know,” she added, “that one or more of them may fall into the wrong hands, and—”

“Nothing we can do about that.” I shrugged with an insouciance I did not feel. “You and Auntie Lu both have copies of my Last Will and Testament. Whatever happens behind those walls, she gets the apartment, and I’m bequeathing you my best Diadem typewriter and my cat. But you’re to burn my coat as my proxy and scatter the ashes where they’ll do the most mischief. No keeping it for yourself, you hag, like I know you want to.”

“Nobody but you and a ragpicker, Dimaguiba, would regard that coat with anything like fondness.”

I haughtily ignored this in favor of picking up one of the stacks of letters on her desk. There were dozens and dozens of them, dating back years—certainly back before I came on, before even Gazala Lal took the Courier’s executive editorial helm. They were all penned by people wanting to find family members who had gone into the Seafall City Laundries (or had been sent there) but who never came back out. Some of the letter writers claimed to have gone to their local police first, where they tried to report their family members as missing persons. In most cases, the police refused to file the reports. And the reports that were filed, nothing ever came of them. The official line is that the Laundries are not doing anything illegal—are, in fact, performing a necessary service for the good of Seafall, the Federation Islands, and all of Southern Leressa—and if a person is known to have been checked into the Laundries, then that person cannot be technically considered “missing.” When one unhappy brother expressed dissatisfaction with this answer, the policeman he was talking to charged him with disorderly conduct.

My boss had discovered the letters, most of them with their envelopes still sealed, stuffed into her predecessor’s overflowing desk drawers and filing cabinets. Her indignation over this deliberate oversight had launched her and a small team—we had dubbed ourselves “The Spyglass,” and considered ourselves the Courier’s sneakiest and slyest investigative journalists—into a fact-finding mission. One of us—Mazzi Shahad—had been dispatched to sniff around the Archabbey at Winterbane, which owned the Seafall City Laundries and operated it from abroad. Valesh Torx was sent to infiltrate the municipal police force—or rather, its secretarial pool—but that did not last long, because although Torx is fantastic at interrupting mayoral bombast to ask that one cutting question, she is terrible at things like logging incoming emergency calls. She’d much rather be out responding to them. Lethe Naype, our regular correspondent at the mayor’s office, in this case has not been undercover at city hall so much as dogged and discreet in her pursuit of this particular line of inquiries. There were rumors that the mayor had had her first husband locked up in the Laundries for ‘dallying with a gentry mistress,’ though most assumed he’d just run away to Southern Leressa when she wouldn’t grant him a divorce. And then there was yours truly, Salissay Dimaguiba. But you, dear Readers, already know all about me.

Gazala Lal had more than just an intellectual stake in this story. She had a cousin, you see, who had gone into the Seafall City Laundries years and years ago, when Lal was still a girl. So had I, for that matter. So many of us have lost a cousin, or sibling, or parent, or friend, or former lover, who was accused of falling under gentry enchantment and sent to the Laundries to be “scrubbed clean.”

In the case of my boss’s cousin, Lal told me: “She was pregnant—barely out of childhood herself. Her stepdad said how she kept leaving her window open, said some gentry vermin crawled over the sill and into her room, and all up inside her, and now she was carrying its changeling. My mama had her doubts, but the folks at the Laundries did a bunch of their so-called tests, and confirmed my cousin’s ‘affliction’ as magical in nature. Been gone ever since. No word, no letter. Nothing. For all I know, she’s buried there.”

When I asked, “You want me to find her?” she answered, “No, Sal. I’ll do that myself. That’s personal. What I want, of course”—and she grinned at me like a fisher cat, like the Gazala Lal I knew, feared, and adored—“is for the Courier to scoop all the other newspapers on this story, regional and otherwise. I also want to blow the Laundries sky-high—figuratively speaking—and you, Dimaguiba, are my last stick of dynamite. Now, we know that the Archabbey at Winterbane owns the building and the land it stands on, and that thirty years ago, the then-Archabbot obtained permissions from the city for a major renovation project on the site. But as far as Mazzi can tell, the current Archabbot does not exert any oversight locally at the Laundries. So. Your job. Go in there. Find out whose boots are on the ground. Who are the current inmates, when did they arrive, what were their supposed ‘symptoms of enchantment,’ how long have they been stuck in there? Who were the ones who came before them—and where did they go? How are they being treated? Most of all—what happens to the babies?”

“The gentry babes,” I corrected her. No one at the Laundries would mistakenly refer to these ‘misbegotten changelings, children of two worlds,’ as ordinary infants.

“All right, then,” my boss said. “What happens to all those so-called ‘gentry babes’? Now, we know it’s not exclusively women and girls—pregnant ones—who get sent to the Laundries—”

“But,” I interrupted, “predominantly.”

She gave a short, sharp nod. “When we had Torx check out all the orphanages in Seafall and the surrounding counties, none of them admitted to taking on newborns from the Laundries. Rumor has it they’re bricking them up in the walls. Others say they’re sold or made into sausages. I want the truth, Dimaguiba.”

“Well, as of tomorrow, I’ve got a whole seven days to get it for you,” I said, a little wryly. On the one hand, seven days seemed nowhere near long enough to penetrate the secrets of an institution that has been around for decades, probably longer. On the other hand, seven days also seemed like a bad bargain out of some nursery rhyme, wherein each day you spent in the Valwode among the gentry meant ten years off your life in the mortal world of Athe. “But,” I added, “I’d like not to end up as a sausage myself, if you get my drift. How’s the escape plan coming?”

She steepled her fingers. “Well, there’s always those letters I wrote. I’m counting on them bearing fruit. But for backup, I got your Auntie Lu on the job.”

“I hope your riot gear is up to code,” I said, and my boss laughed, like she thought I was joking.

Some of you, faithful Readers, may recall my dear old aunt from my previous stories in the Courier—though you may recognize her better by the infamous monicker Lu “the Pit Bull” Dimaguiba, which she earned during the Summer Troubles while helping organize the United Locomotive Engineers to strike for fair wages. The workers won their wage increase, and Auntie Lu made a few very rich, very powerful enemies. But also a few—million—friends, at least a few of whom I was counting on to rally at her call and help me over the walls on the eighth day.

Lal clamped a cigar between her teeth. “Cold, Dimaguiba?”

I unbuttoned the top button of my coat, just to show her I was unafraid. “No, boss. Just old, I think.” I’d done my first exposé at age eighteen, a journalist fresh off the press, the ink still wet. I was now twice that and a tad older.

She shook her head. “Fine wine, Dimaguiba. Fine wine.”

I smiled. “I’m pretty much vinegar at this point, boss. But that’s okay,” I said, sailing off her desk and heading out the door. “I’ll last longer pickled.”

Chapter i. In Which My Disguise as a Wretched One of Seafall Proves Unnervingly Efficacious

They say that the Seafall City Laundries will scrub the enchantment from you, body and soul. They say (and by “they” I mean “anyone wanting to send someone else to the Laundries, while they themselves rest assured of never having to set foot in the place”) that certain of us humans are especially vulnerable to the gentry: we dreamy ones, we dawdlers, we “clouds dressed in homespun” who are more apt to gaze out a window than do our chores. That is how the gentry crawl from their own world, the Valwode, into ours, they say. They nudge their phantasmagoric skulls through the chinks of our self-indulgence. They catch and possess anyone who sits still for too long. Their glamour captivates those who favor beauty and grace over elbow grease and effort. Idleness, in other words, is a gentry malady.

The cure?

Work.

Unpaid work. In the Seafall City Laundries. For the rest of our captive lives.

Of course we know (and by “we” I mean “all of us enlightened readers of this newspaper”) that it’s not just slug-a-beds and slackers who are sent to the Laundries. The Laundries, like Seafall’s own Coalwell Asylum and Oakum Workhouse—institutions our readers will surely recall from previous articles in the Courier’s pages—are most likely just another miserable, underfunded repository for those whom society deems undesirable. Our sex traders. Our beggars. Our “refractory” youths. Our elderly. Our veterans. Our victims of domestic violence. Our immigrant communities. Our citizens with mental or physical illnesses or disabilities.

But unlike Coalwell and Oakum, which are part of a suite of complexes owned by the city and founded with the aim of improving the lives of the poor and the sick—and which still, all too often, fall sadly short of that aim—the Seafall City Laundries is a private institution, funded and run by a religious organization whose seat lies overseas on the Southern Leressan continent! This organization justifies its continued existence by perpetuating the antiquated lie of Three Worlds theory. It further claims that such childish fantasies as the gentry of the Valwode and their downworld goblin-kin neighbors are in fact demonstrably real, and can actively affect our human lives with their magics and bargains! These beliefs are so preposterous that I dread to discover what actual criminal activity these benighted quacks might be getting up to behind their high walls, with none of us the wiser. But discover I will. That is my aim in this investigation.

But to truly examine and evaluate a private establishment like the Laundries, which (again, unlike Coalwell and Oakum) provide no guided tours for nosy visitors and offer not even the slightest pretense of transparency, I must infiltrate its walls. I must present myself to the Laundries as one of the “gentry-afflicted,” in dire need of a good disenchanting. I must join the ranks of “the wretched ones” (as victims of magical malice were euphemistically referred to in days of old). But how to do this? I, Salissay Dimaguiba, who has never lent any credence whatever to the very existence of the Valwode?

It is, I found, easy enough. Even not believing in the gentry, it is no great thing to look afflicted by them. Anyone familiar with a certain branch of Leressan nursery rhyme or the genre of children’s story known as “the gentry tale” knows the way of it. For example:

A sea-glass eye, all glazed and green

That glimpses deep to worlds unseen

A robe of gossamer so fair

A wreath of lilies in her hair

Her tongue on rhymes doth run away

Her limbs to unheard bells doth sway

Her belly round with gentry bairn

Her birthing bed will be her cairn

And so on. There are many more in a similar vein. Not all of them are about young, beautiful women who happened to catch an uncanny enchanter’s eye, and were sickened to the death by spells home-grown in their own wombs. But enough of them.

In my assumed persona of “Sally Dee,” then, I shed the things of Salissay Dimaguiba. Gone my checkered coat and sensible coiffure. Gone the thick stockings and sturdy boots that have carried me from one end of our renowned city to the next. I did manage to secret a stub of pencil and a pad of paper in my undergarments, but that was all.

Barefoot, with my black hair streaming, I headed off as evening fell to meet the Laundries—and my fate for the next seven days. I was wearing an old bathrobe I had picked up at the flea market behind Seafall University. It was made in a style popular in the middle of the last century: a patchwork of every shape, shade, and material imaginable, with brightly embroidered stitches in no discernible pattern, and an irregular hem all round. It was also, moreover, being sixty-something years old, falling apart at the seams. Having bought yesterday’s wilting flowers on the cheap first thing that morning, I wove myself—very badly, I confess—a wreath. I took a pen and drew upon my body arcane symbols: mostly stars and moons and planets. The gentry, as legend has it, having no celestial objects to speak of in the Valwode, have always been fascinated by the boundless skies of Athe. I also draped myself in junk jewelry, bought in bulk at an estate sale.

Seafall isn’t a large city, though it is the largest on the Federation Islands. It was easy enough to walk—or should I say “wander, wander, wander maid / in everlasting twilight shade / and sing, sing, sing the song / of bone bells ringing all night long”—from my quarters in the Shank to the Laundries, which are located further north of the town center, near Avillius Bay. I might have made the journey in twenty-five minutes at a brisk pace, but I meandered and caterwauled and drummed up a bit of an audience. I wanted witnesses.

In particular, let me say, there was a Mrs. Abayomi, bless her, who tried to distract me with promises of supper. “You don’t want to go that way, love,” she said, coaxingly. “Bad things up that way.”

But I tore myself free of her gentle pleading, and told her in a solemn, hollow voice that: “a babe of sticks and tricks doth grow a bramble in my belly, and none but iron nails may root it out again from me.” With tears standing in her kind eyes, she let me go.

Mrs. Abayomi, forgive me. I had to march on; it was my soldierly duty in this ongoing war for the Truth. I do not know how many of Seafall’s “wretched ones” you have saved with your warm food and gentle words, but for the goodness you showed to me on my way, I thank you.

There were others I gathered in my entourage who were not so kind. A few sent their dogs after me. Many laughed, and threw empty cans (steel, after all, is an alloy of iron and carbon, and thus antithetical to the gentry) and other scrap metal. By the time I reached Point Street, I had quite the parade in my wake, and was much dirtier than I had been when I first had set out from my quarters. My wreath hung askew, my feet were coated in muck and mud, I had bruises and cuts on my face, and a few of my inked-on temporary tattoos were smeared with other substances. Of the epithets hurled at me on my way, “gentry babe” was by far the gentlest. When accompanied by a snarl and a fistful of filth, it was not all that gentle.

This is how you look the part of a “wretched one.” You toss yourself like a flower fallen to the gutter. If the Mrs. Abayomis of this world don’t find you first and pluck you out, there are always others in the muck to trample you all the way down.

Thus, I made my way to the Seafall City Laundries.

Chapter ii. In Which I Describe the Seafall City Laundries, Disparage a Mattress, and Meet a Friend.

I will write more at a later date of the formalities of my admission into the Laundries, of the intake papers I had to sign (“just an X there, Mrs. Dee”), and the vials of blood they drew (“gentry infection leaves a trace of nectar in the fluids; we must ascertain the egregiousness of your affliction”), and my impression of the Laundries’ gatekeepers (patronizing yet impersonal, and a bit too fond of bloodletting for my—or anyone’s—comfort). But before I do, I want to share a description, culled from last evening’s impressions—and from my observations on the following day, that is, today—of the Laundries themselves. Orientation alone was a full day’s work!

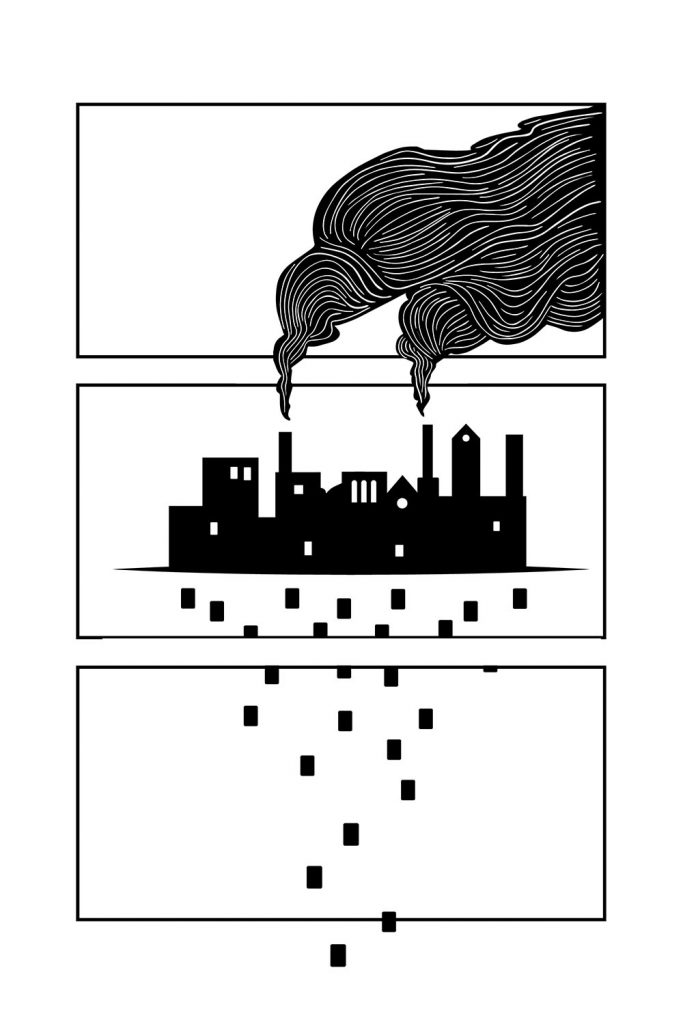

Outside the gates, there is an entry monument carved from a block of Seafall schist (the bedrock of our island), on which in archaic lettering is proclaimed: “Ironwood Institution for Ympsies, Aufs, and Other Waifs of War.” This monument is almost all that is left of the original building, but it gives us a clue into the unyielding mindset of the institution, which has existed, in some form or another, for over four hundred years. Three decades ago, all the old structures were completely torn down, a new brickhouse built upon the foundations by the same architect who designed Oakum Workhouse. Like the monument, the cellars, I believe, are also original to the site. This is important to remember. For all that this place is now called “The Seafall City Laundries,” and seems to be built along more modern lines than many of the buildings that surround it, it remains at its heart and in its depths the same “Ironwood” founded by the Archabbot of Winterbane in days of yore, during the War of the Changelings. The outward appearance may have changed, but the dangerously outdated founding principles are yet rotting away within.

Behind the monument are the iron gates. These forbidding portals are more massive and elaborate even than those that bedeck the main drives of Oak-and-Acorn Street, protecting the “summer cottages” of Seafall’s most prosperous from the hoi polloi. Beyond these heavy, rusting gates is the imposing rectangular brickhouse of the Seafall City Laundries. It is so large it is more like a row of houses, consisting of a main building, a west wing, and an east wing. The brickhouse is three stories high—not including attics or cellars—and lengthwise, takes up half a city block.

The main building is the longest of the three sections. Its entire first floor is dedicated to the workroom, i.e., “the laundries,” and is divided into four sections: for “washing,” “mangling” (or wringing), “ironing,” and “packing,” respectively. The air thrums with the sound of machinery; after spending a day incarcerated in that wall of sound, one’s ears ring with a high piercing whistle that does not go away even in sleep. The air is as steamy as a glass greenhouse built to grow exotic plants from jungle regions, but is not perhaps so conducive to the human respiratory system. The floors are always wet; and so, therefore, are the feet of the workers, for all the long hours they are on their feet at their labor. The ceilings here are high, and I will say there is plenty of light and air from the windows, unlike other buildings of this ilk. Indeed, in the main building, there is no second story proper. Above the workroom, on the third floor, are offices for the administrators, and two parlors for the inmates’ “recreational” use.

Of course “recreational activities” are strictly limited in these areas to things like “recreational mending” and “recreational embroidery,” and let us not forget, the sight-destroying “recreational whitework” that recently drew such attention from the Leressan Lacemakers Guild when they sued the Doornwold Lace Mill for damages to their workers, where long hours of close work and lack of appropriate lighting often resulted in total loss of vision by the age of thirty. All of which recreational activities, you may be sure, bring in money for the Seafall City Laundries above and beyond what their regular services do, and benefit the inmates not at all. Above the third floor are the attics. Below the workroom is the vast coal cellar. The building is not yet fitted out for electricity, though the plumbing is surprisingly modern.

The first floor of the west wing consists of a kitchen, a small beer buttery, the men’s dining hall, and the charity school for “afflicted children.” The men’s dining hall looks out onto the men’s yard. I have not yet seen it for myself, but if it is anything like the women’s yard, it is a bleak enough place. Paved in, with walls as high as the roof, no plants growing—not even weeds—and no benches to sit on. It is a place mostly for pacing alone like a caged beast, or huddling for warmth and gossip, or smoking contraband cigarettes smuggled in by the Laundries’ delivery trucks.

The second and third floor of the west wing are divided into four wards. Wards one and two are for male inmates (there are too few adult males at present to fill all the beds: twelve in total, all elderly and infirm). Wards three and four are for children under twelve, abandoned here by those who claimed these children were “afflicted, accursed, and enchanted.” But none of these “afflicted children,” apparently, were born within the Laundries’ walls.

The east wing is similar to the west with a few exceptions. It has its own kitchen, as well as the women’s dining hall. The only times the denizens of east and west wing meet are during work hours, in the Laundries themselves. They are not permitted even to eat together. Here in the east wing there is also an infirmary, and a confinement room for the “lying-in” of women. There is no nursery for newborn infants. Under the east wing (as with the west, and the main building as well), there is a vast network of cellars for storage, extending into vaults that run under both yards. On the second and third floor of the east wing are wards five through eight, all given over to women.

There are eighteen beds in each ward. The women’s wards are so full that there are some beds sleeping two to a mattress. Each of the eight wards has a nurse recruited from among the afflicted inmates. It was my luck to be assigned ward seven, and thus consigned to Warden Seven’s care. Wardens Five, Six, and Eight are apparently each known for different little cruelties; Five steals blankets; Six wakes you betimes; Eight “is always whispering such things, such things!” as my friend Mrs. Ympsie told me. But our warden, Warden Seven, is a woman of few words. She is brusque but not cruel. Her face is gray and creased; her eyes are beige and bleak. She does her duty and no more. Her gaze never strays to the windows, such as they are.

Ah, the windows! They are all covered in iron mesh, sandwiched on both sides with iron bars. The inner doors of the Seafall City Laundries are all poorly built of creaky, cheap pine. But any door to the outer world is heavy and unyielding. These outer doors, like the gates on Point Street, are forged of wrought iron, with a portcullis fore and aft. Mrs. Ympsie tells me the metals were smelted from star iron—meteorites fallen to Athe from the sky—and thus, being both iron and celestial in origin, are doubly antithetical to any gentry, who might come to the gates “seeking mischief or clamoring after their kin.” The gentry, Mrs. Y explained to me, in her childlike voice, “all dread the distant stars, but crave our neighbor moon.”

This is a typical sort of sentence from Mrs. Ympsie, who claims to be an “Orphan of Ironwood” ever since the War of the Changelings four hundred and thirty-three years back. She also claims that her mother is a Gentry Princess who had lived all her eternal dream of life as a “cloisterwight” inside a Valwodish tree. (Apparently, these trees are only like our mortal trees in appearance. In essence, they are much more like hermit crabs: “shining, tree-like shells that move, albeit slowly, wheresoever their inhabitants will them.”) Mrs. Y’s father, on the other hand, was a poor human logger who bargained his way downworld, where he found her mother’s tree and cut it down—all to steal her for his “Eerie Wife” and keep her as his captive in the human world of Athe.

Mrs. Y did not say what happened to her parents, nor how she came to live in the Laundries. When I asked when she was married, and to whom, to earn her honorific, she replied, “I am married to the Valwode, and forever divorced from it, begotten as I was a gentry babe, and imprisoned in this cage of salt and iron.” She does not seem to have a first name.

This is but one story, of one inmate, here at the Seafall City Laundries. But everyone else with whom I have spoken so far inside these walls has a gentry tale of their own. The tales themselves vary as wildly as one imagination does from the next, but the cult of belief is uniform. There is no one here who so much as doubts the existence of the Three Worlds, or that it is due to the fell magics of the gentry folk from the “Veil Between Worlds” that they are imprisoned here, forever. Attitudes about that also vary: from gratitude at being rescued from magical manipulation, to boiling resentment at being kept here to work against their wills, to fear of being loosed again into an enchanted world, to despair at the thought of never being loosed at all.

But let us return for a moment to Mrs. Ympsie: the first friend I made in this place. Her true age is difficult to discern. For all her abundance of silver hair, her face is fresh and unlined, her voice light and child-like. She might be a prematurely-gray thirty or a well-preserved sixty. There is a gentle, confiding quality about her that immediately drew me. Oh, yes: she spun me her gentry tales, inviting me to play with her in the false but beautiful citadel she has built to keep her harsh reality at bay. But despite all this, I knew her for my friend at once. And she knew—for she told me—that I was hers as well.

Perhaps you, too, Reader, have experienced such an instant friendship: it is a kind of love at first sight—though not of an amatory nature. Almost at a glance, in a single flash of warm familiarity, I understood that in Mrs. Y I had discovered a vessel in whom I might safely repose my innermost confidences. There was no initiation rite to our secret sisterhood, no more than the touch of a hand in passing, an exchange of smiles. I wanted to tell her everything. Indeed, I found it difficult to repeat my carefully constructed fabrications for coming here, which I had uttered so blithely earlier that day to the Laundries’ administrators. But no investigative journalist of The Spyglass risks endangering her assignment by leaking word of it betimes. I said instead that I had come to the Laundries seeking out lost gentry babes, and she seemed to accept this.

Mrs. Y and I were assigned the same mattress in ward seven. It was the closest bed to the window, and we whispered like schoolgirls into the night. When she finally fell asleep, I wrote down all my notes in the shorthand code I have developed over my many years in journalism.

Sleeping, I fear, will prove difficult. Our mattress, which is representative of the rest, is stuffed with lumpen, greasy flocks. Though the bed linen is clean and pressed and well-mended, I am sure that we share our mattress not only with each other but with a company of invisible vermin. I make here a final note to myself that I must necessarily be shearing my own “flocks” and bathing in vinegar come my freedom on the eighth day.

Chapter iii. In Which I Am Placed with the Washers, Go Snooping—and Get Caught!

Breakfast was beef broth and bread, which was not as awful as I had feared. You have of course, dear Reader, already read Valesh Torx’s descriptions of the flyblown “black breads” in her exposé of Coalwell Asylum, and likewise Mazzi Shahad’s revolting account of the burnt porridge at Oakum Workhouse “with sawdust mixed in.” Here the meal was at least nourishing, the portions unstinting.

I did miss the coffee my boss and I always picked up from the Hart and Horn Automat near the Courier’s headquarters. By the time breakfast was over and I was placed with the washers in the Laundries, I had a slight headache. This would assuredly grow worse over the next few mornings if I continued to abstain from my circulatory system’s traditional exchange of sluggish sleepy blood for hot black caffeinated brew, but for now my symptoms of withdrawal proved no more than a mild irritant.

The previous evening, while I was being admitted to the Laundries, I was told that sometime today I would be taken off my work shift and called in for an in-depth interview with the “abbess.” I was hopeful of finding an opportunity to lose myself in the corridors either on my way to or from my appointment, and explore as much of the main building as I could for as long as I remained undiscovered. Until then, I had much to occupy myself. I wanted to observe, and if I could manage it, interview the handful of women from ward seven who worked the same washers’ shift as I. There were no rules governing conversation between inmates so long as the work was done efficiently.

I found, however, that the intense physical labor as well as noise of all the machines were themselves natural deterrents, especially as the day wore on. Some inmates were dour and silent throughout, but others, in the early hours, were willing enough to talk, and we shouted our questions and answers at each other as we worked. Conversation was far more cheerful and lucid than I had been expecting, given the whispering in the ward the previous evening. We spoke mostly about the work itself, sprinkled with news from the outside (this I happily provided, being such a recent installation), and the usual complaints about wanting more food and better clothes. No one who had spoken to me of their enchantments either last night or in the chill dawn of that very morning, when the door of our ward was locked and we lay in its iron-barred darkness, spoke of magic now. It was as if the subject was entirely forgotten.

No child was present in the workroom; I was told that they had lessons at the charity school in the morning, and then housekeeping chores in the afternoon: helping to change linens and prepare food and wash floors and so forth. Admittedly, these children are not worked so hard here at the Laundries as are the young “holdy-moldies,” and “sticker-ups” and “warming-in” kids of the glass factories, or the bean stringers in the canneries who work eighteen to twenty hour days, or the tiny but nimble coal breakers in the Candletown Company mines whose lives are so dreadfully dangerous. At least here they attend the charity school—though if all they are taught is Three Worlds claptrap, then their education is next door to absolutely useless. I can just imagine my Auntie Lu climbing atop one of these washing machines, and agitating for child labor legislation right here among these wretched ones. But since she is not here to bellow like a distressed pit bull bent on protecting her young, I will keep my silent notes and add them to the growing list of atrocities I have witnessed against the youth of Seafall. The problem is not local but systemic; almost twenty percent of all Leressan laborers are under the age of sixteen, and these workers make less money and have fewer rights than their adult counterparts. But that is a story for a different day.

My new friend Mrs. Ympsie does not herself work in the Laundries. She was apparently an embroidery artist of no mean talent, and spends her days in one of the third-floor parlors doing fancy work. Today, she told me this morning, she would be, in her own inimitable words, “stitching spells for the hem of a happy bride, but gods help the groom who strays from her side,” and so, I would probably not see her again until after dinner.

The washing room was a cacophonous museum of progressive technologies. In it, there were almost as many kinds of washing machines as there were people to work them. Many of them were old-fashioned. Most, by the look of them, had been donated or else had accumulated over the last century. The newest machines were large iron drums with hand cranks for agitating the clothes in soap and water. Some of these rotating drums had mangles built in, and these were kept closest to the door in the partition that led to the mangling room, where the rest of the wringing was done. The clothes were then rolled into the ironing and packing rooms beyond. But there were also plain wooden washboards over which clothes were worked with washer skates worn over the hands. There were machines with floating dolly agitators, machines with swiping levers along the bottom, machines with racks and pinions, machines with wheels and cones, and machines with small fires burning swelter-skelter beneath them: all with gears and cranks and pulleys and levers that set up such raucous, pitchy, clinking, creaking, roaring racket in that high-ceilinged room that the bony plates of my head felt jarred loose from their sutures.

I am not, as my colleagues might tell you, fond of any exercise more arduous than knocking on a door and asking for an interview, except for that one year in my late twenties when Gazala Lal challenged me to write a story on aerial locomotion, and I got my pilot’s license to fly hot air balloons. Even in that year of flight, I did not work so hard as I did this morning in the washing room. I have never been so hot, so slopping, sloshing wet, so tired, with such a clamor in my head. But I will also say this: despite the noise, despite the backbreaking, muscle-tearing work, there was also an oddly jubilant rhythm in that washing room, a song within that thunderous noise. I was separate from it, and yet seized by it. It was as if a part of me stood outside of myself, in thrall to this song, this celebration that lauded human invention and human industry, while my body labored somewhere below me.

If I did believe in the gentry, I could believe also that this song might cure whatever spell they had set upon me. It took over me bodily, worked me harder than I was willing to work, and left me, by luncheon, wrung-out and wet and trembling. Laundry is not for the weak.

But I did not mean to waste my afternoon plunged to the elbows in suds. I meant to go exploring. And so, after getting my second (or more like seventh) wind back, I went on an exploratory journey to the toilets. On my way there, I also nosed around the infirmary, the kitchen, and lastly, the confinement room, where a pregnant young woman was bound to the iron rails of her bed by manacles of iron.

There are times, in my work, when I grow so angry I feel throttled, as if my own fury has molten hands wrapped around my throat from the inside, squeezing. When I was younger, I was much jollier, and perhaps much more callous. But I have grown only more outraged with age and experience.

I saw the iron manacles, the swollen belly, the sharp features and sunken eyes of the woman, and I felt my anger become a destroying beam. It took me over, directed my movements, and puppeteered me into the room and over to the bed, where I bent over her and whispered, “Can I help you?” My voice was trembling with the force of holding back a battle cry.

That was when she looked at me. I thought—just for a moment—that her eyes flashed green in the dark, like a wolf’s. Then she turned her face away. The closer I came to her, the less I smelled the overpowering and pervasive odor of the room itself—old blood and sour milk and the fug that settles in an inner chamber with no windows or ducts to conduct clean air into or through it—and the more I smelled a scent like cream and violets, like lavender and wine, like antique silk and new-cut grass and heavy velvet and crushed autumn leaves.

“You?” Her words were bitter. She kept those strange (sea-glass) eyes fixed on the wall, away from me. “What can you do, mortal?”

“I—” I began.

“Mrs. Dee, is it?” said a kindly voice behind me. I say “kindly” but it was a kindness that chilled the nerves running through my spine and made my vertebrae crackle like icicles. “I am Pursuivant Hententious, here to bring you to your appointment. Her Holiness, Abbess Caelestis the Fifth, will see you now.”

Chapter iv. In Which I Meet the abbess of Ironwood Institution, and She Surprises Me

The office of the abbess was off the women’s yard in the east wing. It was a stark place, possessing nothing but what was absolutely necessary. Even the abbess’s chair was the splinteriest, rigidest, narrowest of all the chairs I’d seen so far in the Laundries. Her desk was an old scarred farm table, covered in neat piles of paperwork: the desk of a very busy woman. Battered steel filing cabinets lined the southern wall, blocking the only windows that would have otherwise looked out upon the outer world.

But the only windows free of iron mesh or iron bars or steel cabinets presided over the gloomy grayscape of the walled-in women’s yard, where, no doubt, the abbess liked to keep an eye on her charges. The west wall of the office was taken up with an extra linen wardrobe and a gigantic hobnail safe. The east wall framed a set of large, propped-open double doors that opened into the corridor conducting back to the women’s dining hall in the main building.

When the pursuivant with the cold-cracking voice ushered me in for my appointment, I noticed a key cabinet bolted to the office wall next to the doors. Like everything else in the Laundries, it was ancient, heavy, worn: a wooden rectangle divided into dozens of dovecotes, each with a tagged key hanging from a tagged hook.

At first sight of this cabinet, I knew a craving—a thirst so powerful I could almost call it a lust—to sneak back into the office at night, steal all the keys, and use them to throw open every door in the Seafall City Laundries. I would light lamps in every room, air out all its secrets, let everyone locked within its walls wander free, and then drop the keys into the nearest privy on my way out. My way back. To my real life, my desk, my apartment—and best, the frantic and fast-paced (well, more like tedious, slogging, and methodical) culture of the Courier’s newsroom.

But stealing keys would not actually unlock the mysteries of the Laundries. That was what exposés were for.

I forgot all about the key cabinet the moment I set my eyes on Her Holiness, Abbess Caelestis the Fifth, sitting behind her desk like a bolt of lightning trapped inside a pillar of ice, wearing a neat suit of brown and gray wool. She was smiling.

“Mrs. Dee, welcome,” the abbess told me pleasantly. “Your blood test results came back only an hour ago. I am happy to inform you that you are free of gentry affliction.”

I admit I stared for some time, my mind a perfect blank. I had entered this office willing to tell any lie, ready to spout any number of extemporaneous nursery rhymes, to rest my hands upon my belly and lead from my navel. But with just a few words, the abbess had snapped that horn at the pedicle. I took the chair she offered me in silence, and sat with my hands folded in my lap, my brain whirring like a Dashwheel washing machine.

“How do you know?” I asked at last, roughly, sullenly. Almost without thinking about it, I had slipped into the rougher, swingier, gutter-slang-style of speech I had grown up with. It was easier than improvising rhymes on the spot, and it would also serve. “Mrs. Y in ward seven don’t seem any more afflicted than me, and she’s been here all her life. Who’s to say I ain’t accursed too?”

At my mention of Mrs. Ympsie, a tiny frown of concentration appeared on the abbess’s forehead. Her eyes glazed, as if she were trying to remember a word or a name that hovered on the tip of her tongue. But then her frown smoothed out, and her gaze sharpened and brightened again, not with amusement or welcome exactly, but with an intense interest in the present moment, and in the person sitting before her.

“I see this news upsets you, Mrs. Dee. But I assure you, we immediately send all blood samples from incoming supplicants to our leading-edge laboratories at Winterbane. The results are rarely wrong.”

She pronounced her rarely, I noted, with the canyonlike resonance of never. Note her use of “supplicant” instead “inmate” or “beggar” (like “pursuivant” in place of “orderly” or “guardian”). It is my belief, dear Reader, that this was to set the argot of the Laundries apart from that of the other asylums and workhouses of Seafall, a specialized language that reinforces and cements the cult of faith that rules this place.

“Labs!” I snorted. “What good are they? Magic ain’t no science. A child could tell you that!”

The abbess’s smile vanished from her lean face, an expression of alarming enthusiasm suffusing it instead. No, not just enthusiasm. Fanaticism. Either she was a greater actress than the stage empress Adeodat “the Divine” Arlette, or else she believed her own Three Worlds hokum with the same fervor I had witnessed in the supplicants she presided over. I wondered, then, who had been brainwashing whom.

“Perhaps not in centuries past, Mrs. Dee, but I assure you, human ingenuity does not sit stagnant! In days of old, ascetics of my order would taste the blood of the afflicted, testing for what we used to call ‘the sweetening.’ These days, of course, any testing we do to detect mellifemia is contactless. We are developing equipment to isolate and identify the compounds in afflicted blood that cause this chemical change—and others: like the development of light-emitting enzymes, similar to the luciferases found in certain bioluminescent organisms, in enchanted blood, that make it sparkle and glow in the dark. Other effects of enchantment are more unpredictable. Sometimes, for example, when afflicted blood is injected into lab mice, it gives them powers of human speech, or allows them to breathe fire, or causes silver scales to grow in place of their fur. We are attempting to control for that change. But your blood,” she finished, her expression immediately fading from its live-wire avidity to a pleasant facade of neutrality, “was perfectly ordinary. Congratulations.”

I wanted to pound both fists on her desk and roar in her face. How dared she try and force-feed me—me, Salissay Dimaguiba!—this codswallop, this snake oil, this gentry tale tricked up in quacksalver panache—and expect me to swallow it holus bolus? Their leading-edge labs at Winterbane indeed! The Archabbess of Winterbane oversaw all abbeys and monasteries in Southern Leressa and the Federation Islands, and all the smaller communities of worship who prayed to a hodgepodge of gods, saints, and angels so outmoded they were practically interchangeable, begging for the protection of these imaginary invisible forces against the equally imaginary forces of the gentry and koboldkin, not to mention demons from the Seven Hells, and the relentless entropy of the cosmos. Winterbane was so far from the leading edge of anything technological, it was probably still operating on steam power and clockwork while the rest of the world was running on combustion engines and isolating radium through electrolysis. Winterbane’s Archabbess, like this less important but still oddly terrifying abbess sitting so calmly before me now, had every motivation not only to perpetuate but to incentivize Three Worlds myth in order to keep her religion, and herself, relevant.

But neither Sally Dee nor I would allow ourselves to be dismissed from the Seafall City Laundries with such a pat answer. We were made of sterner stuff. And we had a mission.

“Ma’am.” I tried for more humility this time, maybe even a little desperation. I looked straight into the abbess’s eyes, keeping my own gaze steady and earnest. Her pupils were too large, as if she had recently taken belladonna drops. Her colorless irises were thin rims at the outer edge of blackness. “Please don’t send me back out there. I got nothing. Nothing but this baby on the way. At my age, ma’am—what else am I gonna do?”

“There are other institutions,” suggested the abbess, not ungently. “The Working Women’s Almshouse, for one. They would have given you a place in their wards without any need for you to resort to rhyme-raving or elaborate deceptions.” She gestured to my tattered robe and tangled hair and cheap beads. “If you like, Mrs. Dee, we can arrange for your transportation to such housing later tonight, after dark. It is best that the other supplicants do not witness their fellows departing the premises; they themselves do not have the option. It makes them restless.”

I made a mental note to relay this information to Gazala Lal. It seemed there was some sort of selection process at work here at the Seafall City Laundries. Perhaps at present they needed more incoming males to be “afflicted,” and were therefore offloading any unwanted females onto other charitable institutions. It was possible, then, that Lal’s young cousin, after being admitted to the Laundries and deemed enchanted, had revealed the worst of her stepfather’s abuses and was moved in secret to some other place. She might even now be living free under an assumed name. Possibly, somewhere in this office, there was paperwork to that effect.

But for now, that was not the business at hand. The last thing I wanted was to be booted out of this place under cover of night, before I had a chance to learn anything.

“That almshouse!” I spat, rising to my feet with clenched fists. “Cursed is what it is! Stink of death on it. Ain’t you hear about all them women disappearing? Bunch of girls dying of phossy jaw in the Matchstick Ward, and what do they do? Just upped and vanished in the night. Not a one of ’em well enough to get up and walk out on her own, much less stroll past the night guard and hail a taxi to nowhere.”

I had no trouble railing on about this subject, as it is (as you are no doubt aware, dear Reader) a perpetually open wound upon my heart. You will recall the shocking events of five years ago, when I was following up on an article I had written about millionaire philanthropist Tracy Mannering’s work on the expansion of the Seafall City Working Women’s Almshouse. I thought I would be covering the official opening of a new ward dedicated to the treatment of factory women poisoned by the fumes of white phosphorus. Instead, I discovered that half a dozen very sick women—women, as it happened, who were suffering from phosphorus necrosis of the jaw—had disappeared from their beds one moonless night. The nurse who was working reception that evening said that Miss Desdemona Mannering, only daughter and heir of Tracy Mannering and coal magnate H. H. Mannering, had swaggered into the almshouse sometime around midnight and demanded that she be allowed to visit the Matchstick Ward. The next thing the nurse knew, every bed in that ward was empty of its dying body. No sign remained that anyone had ever inhabited it, but neither was there any sign of anyone having exited the building. And no one has ever seen or heard of those sick women, or of Desdemona Mannering, ever again.

“Oh, ma’am—don’t you see?” I begged the abbess now. “It’s better here! Far better to be here, and safe, than in that hell-hole where goblins come to steal you in the night!”

“Our mission at Ironwood Institution is very clear, Mrs. Dee, and very serious. The work we do here is designed specifically to help those afflicted with gentry malice. We promote will through work. The will to live in this world and no other. Most humans,” the abbess added pityingly, “prefer the beautiful dream that kills them to the brutality of a world that makes us stronger. Those gentry wiles, those hazy, poisonous luxuries that sap our strength and enervate our vitality, need to be sweated out! What better cure for the Valwode’s dream than hard human labor? What better safeguard against enchantment than to surround our supplicants with articles that the gentry find most repellent: iron machinery, running water, salt of borax? I assure you, for the recently enchanted, a thorough immersion in our workhouse program is a panpharmacon for all magical malisons! Converting Ironwood Institute into a laundry service for the City of Seafall was one of my first modernizations when I came here thirty years ago. We pride ourselves on being a self-sustaining institution, Mrs. Dee, in partnership with but not beholden to our superiors at Winterbane. And so we will continue to be—so long as we do not exceed our mission! Our women’s wards are full as it is; we have no place for you.”

“Oh!” I cried, and sprang to my feet, my hands threaded into the tangles of my hair. “How I wish the gentry’d come to me! Better jinxed by some jolly auf than crammed with child by a no-good husband. One who’s gone and left me for some chippy with bigger titties than brains. A baby! His! At my age! Oh, I wish it was a gentry babe!” I said bitterly. “I wish I’d met a magic prince and drunk his nectar deep!”

This was a gamble; I was wagering my continued investigation on the idea that the abbess was in fact a true Three Worlds believer, and thus one who would hear in my words and see in my face the need to save me from myself. (Or else, having cozened so many others with her lie, she would have no choice but to play along, at least for the present.) And truly, my words did seem to perturb her. Reaching across her rough desk—she had to stand up to do so—she took both my hands in hers.

“Mrs. Dee, please. I can tell you—most solemnly—that it would not be better to be accursed. Do not invite it! The gentry are an invasive species. Deadly. To yourself, to your little baby—to our whole world! Any interaction with the Valwode, any bargain, any exchange, invites them in. They are always listening at the windows of our desire. They are always pressing their unnatural ears to the walls between our worlds. Tapping for cracks. Looking for chinks. Once you fall under gentry enchantment, Sally, you are doubly susceptible to it. Your body is compromised—your skin, your bones, your blood, your very genetic material becomes a vulnerability in the barrier that keeps Athe and the Valwode discrete from each other. We need to bolt our doors and shutter our windows firmly against their prying eyes. You must be strong.”

This was promising, I thought, and immediately broke down in tears. (This is a talent, I confess, that I have purposely developed over the years.)

“I can’t!” I wailed. “I just can’t anymore, ma’am. I’m tired. I’m so tired. Just let me stay! Please let me stay! Just till this baby’s out of me?”

Or at least, I thought but did not say, for the next six days anyway.

Slowly, the abbess sank down in her chair again, inviting me with a gesture to do the same.

“We do not have the facilities,” she said slowly, “to support newborn human babies. The children of our charity school have all themselves been afflicted. Some of them were stolen downworld as infants and then abandoned when their gentry kidnappers grew bored with them. Some were born enchanted as part of a bargain their parents made. You would have to leave this place after the birth of your own child and take it to an orphanage of your choosing—unless you decide, after all, to keep it. Again, there are other institutions that will help you make these decisions. But…until then—”

I looked at her with bright hope. I did not even need to manufacture the expression.

She finished, “We will harbor you, Mrs. Dee. But,” she admonished me, “no more sneaking around the east wing when you are meant to be working! The confinement room is not a safe place! You risk accidentally exposing yourself to the enchanted blood of the afflicted—or worse. You do not want to be like our lab mice, do you, and risk an arbitrary gross physical transformation?”

“Yes, ma’am. I mean, no, ma’am.”

“Mrs. Dee,” the abbess said severely, “I must tell you that I find your apparent determination to seek affliction at the least setback most disturbing. To combat this tendency, may I suggest”—her “suggestion” had the strong whiff of “mandate” about it—“that in your recreational hours, you avail yourself of the materials in our library? We keep our archives in the parlors above the workroom. You might”—and her hidden ought here was as clanking-loud as a dozen iron washtubs—“read aloud from the books you find there to any supplicants sitting at their mending. You will thus reinforce your own education by disseminating it to the truly afflicted.”

This stirred me to excitement. Archives! Probably all useless tracts and pamphlets—but still, there might be something interesting (or damning) in them. Also, I knew Mrs. Ympsie did her embroidery in those parlors. I was eager to spend all the hours I could with my new friend, and continue our absorbing conversation—fraught though it was with the mantic and metaphoric.

“Yes, ma’am. Will do. Thank you, ma’am.”

“Off you go now.” She waved her hand, scooting a stack of paper nearer to her on the desk. As she did so, just for a second, she reminded me of Gazala Lal. I turned to leave, but had not made it across the threshold before she called out to me again: “Oh! I almost forgot. A moment, please, Mrs. Dee.”

Schooling my face, I spun about, and saw that the abbess had stepped away from her desk and was crossing over to the linen wardrobe. Unlocking its doors, she removed one small glass jar of many, and found a matching metal lid for it. Back at her desk, she fitted the lid with a new tag, on which she had printed today’s date and the name Sally Dee.

“When you leave my office, my pursuivant will see you to the nearest water closet. Please fill this jar with your urine. We will send it to our labs at Winterbane as soon as possible.”

“You want my piss?” I asked flatly. Never yet this day had Sally Dee and I had been in such harmonious agreement of character. “What for?”

The abbess smiled, and though it was the right motion—her lips curving up and the corners of her eyes crinkling—all the fervent lightning of her being was once more firmly trapped behind a pillar of ice. “As you have put yourself into our hands, Mrs. Dee, your welfare has become our sacred responsibility. We want to make sure that both you and your baby are as healthy as can be. We do this by something called urinalysis.”

I took the jar gingerly. “But, ma’am. What if I can’t, you know…go?”

“Take all the time you need. Pursuivant Hententious will wait.”

Chapter v. In Which My Situation Takes a Grave Turn—Possibly Literally!

Mrs. Ympsie sat at the edge of the couch, her spine as straight as the needle she plied. Today she was working on a length of material meant either for a bridal sheet or a very fine table cloth; I could not tell. Her embroidery needles were unusual, made not of steel but of bone. Her wooden sewing box, which sat at her feet, overspilled with spools of silken thread of every pale shade. Individually, any of these spools might be taken for plain white thread. Collectively, after the threads were set against each other on a ground fabric of white linen, and stitched into complex scenes thronging with flowers and birds, beasts and insects, fungi and fish, as well as figures that seemed to be all of these at once but human as well, they glinted with a delicate, ethereal beauty, like a painting rendered in watercolors.

Saving Mrs. Y’s presence, the recreational parlor was empty of company: a pleasant surprise. This was my fourth day at the Seafall City Laundries. My shift was done and it was two whole hours till supper. I was ravenous, my body sore and throbbing from moving hundreds of pounds of sopping wet cloth. My ears were ringing, my hands were wrinkled and chapped, and my brain was absolutely on fire from another day of unabated noise without so much as a single sip of coffee to make life bearable. The dull headache I’d borne with since my first morning here had culminated in a sparkling, spiking migraine last night. Even my eyelids felt bruised and tired.

Not too tired, however, to read. Today, for my abbess-mandated scholarship (and for purposes of my own investigation), I selected a slender volume by the title of Holy Pricksters: A Short History of the Order of Venipuncturists, Founded by Saint Avillius III, Archabbot of Winterbane. Taking the book, I went to sit on a little footstool near the window, where the light (such as it was) was best. Mindful of the abbess’s instructions, I inquired of Mrs. Y whether she wanted me to read to her. I expected her to answer, as she usually did, with something along the lines of, “What is history to you is merely unpleasant memories to me; I do not care for the dreams such stuff would drum up.”

But this afternoon, my friend gave me a slow, regretful nod.

“Yes, that one will do you good in days to come. It will help you understand her.”

Mrs. Y’s idiosyncratic way of speaking is difficult to convey on the page. But no matter how opaque her pronouncements, I was always able to intuit her meaning. For example, I understood that by “her,” Mrs. Ympsie meant Her Holiness, Abbess Caelestis the Fifth, and that she dared not speak even her title lest it somehow summon the woman’s attention to us. Furthermore, I understood that Mrs. Y was concerned for my safety, today in particular, and in a way that she had not been for the past four days. This did make me uneasy, but I had learned that questioning my friend too closely forced her into deep retreat. (Doubtless she would claim she got this from her mother’s—the cloisterwight’s—side of the family.) I was confident that Mrs. Y would tell me all of what she knew, and gladly, but in her own time, in her own way. She might speak in fable and folklore, but I had no doubt that whatever she wanted me to comprehend, I would, in the end, comprehend in full.

And so, I opened the book and began to read aloud:

“An elite force of ascetics, the Order of Venipuncturists served as soldier-priests, gentry-hunters, and inquisitors errant for the Archabbot of Winterbane during the War of the Changelings. The lay term ‘pricksters’ referred to the syringes that the venipuncturist priests wore on bandoliers across their chests. A common zeal for rooting out downworld magic from Athe, and destroying it for all and for good, united the venipuncturist priests in their purpose; their main duty, as they saw it, was to ferret out rumors of Valwodish magic, draw vials of blood from any human suspected of entering into unholy contact with the gentry, and bear away these samples to the Archabbey at Winterbane, whereupon the samples would undergo a barrage of bespoke tests. Meanwhile, persons suspected of gentry affliction would be kept imprisoned until proven innocent of magical influence. If proven otherwise, they were summarily executed. In the written and musical literature of this era, depictions of these ‘pricksters’ varied; they might figure as villains or saints or even bumbling clowns, depending on which story was being told, or which song was being sung—and on whom was singing it.”

I put the book down a moment and mused aloud, “You know, Mrs. Y, it is amazing to me that in this New Century of enlightenment and industry, the Order of Venipuncturists was never dissolved. It’s utterly obsolete. And yet, listen to this, their founding mission: To protect the World of Athe from invasion by the Gentry of the Valwode, to seal Athe off from the influence of the Veil Between Worlds, and to save all moral and mortal people from uncanny corruption. Why, the abbess said practically this same thing to me during our appointment! It’s like she’s walked right out of a bygone era, bandolier and all.”

Mrs. Y regarded me with eyes as purple as pansies. Though the room was dim with the lack of natural or artificial light, I could see the color of her eyes as clearly as if I were strolling in the botanical gardens on a sunny afternoon.

“Her order has existed for four hundred and thirty-three years,” she told me. “She sees herself as an Avillius reborn, but with better tools to fulfill his founding mission. Through her work at the Winterbane laboratories, she seeks to understand the genetic differences between what she considers true humans and those whose humanity has been, as she calls it, compromised by enchantment. As for the rest of us—the ill-begotten halflings, the monstrous get of two worlds, the gentry babes—her calling, as she sees it, is to prevent the spread of our inborn affliction to others by whatever means necessary.”

“By whatever means necessary,” I repeated. I wanted to take my pencil and pad of paper out from their concealment in my underthings and jot down all my notes immediately. But that could wait, I knew, till tonight, when everyone else was asleep and I was alone with my thoughts. “What, exactly, does that entail? Captivity, obviously. The exploitation of labor.” I gestured at the dour parlor with its linoleum floors and peeling wallpaper. “What else? Compulsory sterilization? Eugenics experiments?” I lowered my voice. “Murder?”

Mrs. Ympsie hesitated. Then, she slipped her needle into the edge of her work, securing it for when she would pick it up again. She crossed from the stiff couch to the window where I sat, and dropped to her knees before me so that we were eye to eye. She was so small. A small, bright thing.

“Salissay,” she whispered, although I could not remember ever telling her my full name. That gave me an odd feeling, like remembering every word that rhymed with the word you actually wanted but not the word itself, or mistaking last night’s dream for a recent memory in the company of someone who knew better. “Oh, I wish…how I wish that the shadow I bend over myself might extend over you. But the half of me that is my mother—though long of life—is short of power. The half of me that is my father weakens and grows old. And all of me is so afraid, and always has been.”

How childlike she looked then, despite her words. She was scarcely more than four and a half feet high, and slight withal, her bones as delicate as her needles. Her silver hair was bright as a lamp, bright as the moon, and it seemed to blur as I stroked it. As I murmured assurances that all would be well, I was aware that we both were crying, although I did not know why, and then suddenly she was standing, and we were covering our ears with our hands. In every room of Ironwood Institution, from the (heretofore meaningless) metal trumpets I had observed suspended above each exit door, there came the dinosaurian clangor of foghorns.

“What is that?” I shouted, barely able to hear myself.

“The alarm. They are coming.” Standing swiftly, Mrs. Ympsie stepped in front of me, and spread her arms wide, making her slight body a barricade to bar me from view.

But the abbess, flanked by two pursuivants—Hententious and one whose name I did not know—thundered into the room as large and loud as the horns sounding through the brickhouse. They headed straight for me, shoving my friend aside as if she were no more substantial than dust motes floating in a moonbeam. The pursuivants hauled me up from the footstool and bore me upright between them. My feet dangled, not touching the floor. I did not realize that I still held the Holy Pricksters book until Abbess Caelestis the Fifth plucked it from my hands. It was slim, as I mentioned, and bound in soft leather, so it was more shocking than painful when the abbess used it to strike me across the face.

“That is for deceit!” Her voice was low but flowing with electricity, her smile not a smile at all but a grimace of almost ecstatic excitement. “And that,” she struck again, “is to wake you from your enchantment, Mrs. Dee!”

“Enchantment?” I gasped, striving mightily to pull the persona of Sally Dee over me, to show not the abrupt, roaring rage that had lifted its head from out my chest to bear its scimitar teeth, but only terror and pleading and a bewildered subservience. “Me? Ma’am?”

She was peering into my eyes as though she could suck them out through her own. After a moment, she withdrew, slowly shaking her head. I saw now, that over her neat suit, the abbess had flung a leather bandolier glittering with vials and syringes, as if when the emergency horns had sounded, she had arrayed herself for war in the time-honored manner of all pricksters.

“Alas, Mrs. Dee. You are too far gone. The green glaze is upon your eyes. Were I to draw your blood for testing today, it would taste sweeter than maple syrup.”

She was tapping and caressing an empty syringe on her bandolier as if her fingers itched with longing. I do not know if it was that or the anticipatory look on her face—all I knew is, the next second, I lost my temper. I bucked, kicking out hard enough that the abbess stumbled back, her hands flailing away from her needles. We glared at each other, she into my blazing eyes and slap-reddened cheeks, I into her too-large pupils and peeled-back lips. My ears were full of foghorns.

“I wish my news were otherwise.” Her voice was calm again, even regretful. “I wish you had been pregnant, as you lied that you were. But urinalysis does not lie.”

“So it’s not just blood—now piss talks to you?” I spat, feeling the last rags of Sally Dee burning away in the acid of my vitriol. “Another of your quackeries, Caelestis? It told you my womb was empty, did it, that I was enchanted up to my ears? Did it make your lab rats sing arias and predict the future too?”

The abbess unsnapped a familiar glass jar full of a familiar fluid from her bandolier and thrust it in my face. I reared back, not wanting the thing too near my nose.

“A pregnant woman’s urine,” she told me, “when injected into a juvenile female mouse, causes her to go into heat.” The abbess’s cadences were exact and didactic, as if she were my disappointed schoolteacher and I her young delinquent called in for detention. “The process takes three to four days. While we waited on those results—for the sake of your health and well-being, Mrs. Dee—we performed a series of routine tests on your urine for other anomalies: cancers, diabetes, infection, and—yes—enchantment.”

“Why bother? You tested me for that already!”

The abbess stepped back to appraise me. Her pursuivants did not relax their grip, nor did they let my swinging feet touch the ground. “This is a war,” she said softly. “A war of centuries-long standing. We cannot be too vigilant. Look at yourself, Mrs. Dee. When you came to our doors, you were not enchanted. You were innocent of that corruption, at least, if not of deceit. But somehow, since passing through these walls—these walls that were built as a bastion of safety, each brick blessed to protect against the foulest enchantments—you have been in direct contact with one of the gentry. It has extended its malign influence over you. You have exposed a weakness in our stronghold. We have been infiltrated, Mrs. Dee. You have been infected. We must find the gentry carrier. We must quarantine you from the others, and do our best to arrest the advancement of your enchantment. Recall, when we met, how I told you that the afflicted are doubly vulnerable. Everyone who came to us here for protection is now in danger of relapsing into re-enchantment, and through their compromised bodies, opening new chinks in the barrier between our worlds. Ironwood Institution will go from being the safest place on Athe to being a blight upon it: a deadly vortex of Valwodish contamination. Until we discover the source of your current affliction, the Laundries are on lockdown. The supplicants are consigned to their wards. Everyone must be re-examined for signs of enchantment. Access to the yards is prohibited. School is canceled. The workroom is shut down. The gates are barred. But you can help us end these restrictions quickly, Mrs. Dee. Tell us who it was that enchanted you. Tell us where and how it laid its hands upon you, and when it cast you under its thrall.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about!”

The abbess ignored my words, but continued to study my face. I wanted to blink my eyes rapidly to prove that they were, as they had always been, plain brown, without a hint of sea-glass green. “Pursuivant Hententious found you in the confinement room when he came to bring you in for your appointment. But that supplicant’s labors had not yet commenced. She was merely human—though a thoroughly enchanted one; her cursed gentry babe had yet to be born on that day. The woman is gone now, safe at one of our other locations, and showing signs at last of recovery. Where else have you been skulking? Who else have you been talking to?”

Now I smiled at her—the kind of smile that once earned me a police baton in the face at a suffragist rally. I never got the blood out of the white gown I had been wearing that day, in solidarity with the other marchers. Instead, I cut out the stain in a piece the size of a quilt square, and framed it. It hangs above my desk at the Courier, right there with my Quill Award for Excellence in Journalism. I smiled, and the abbess looked around for the book she had dropped, as if she wanted to smack me with it again.

“Who, me?” I goaded her. “I talk to everyone. I’m a friendly gal. But I got to say, Caelestis—no one talks back like you. Check your own urine lately?”

That earned me a quick, cruel kidney punch from Hententious. Stars burst before my eyes, and a deeper, stranger vision: an elusive flash of silver, a pair of slender hands combing my hair, someone whispering urgently in my ear. As if she had seen straight into my skull, had observed that moonbright flash for herself, the abbess leaned in, looking avaricious.

“That was it,” she hissed. “Just for a moment. Your eyes, Sally Dee, were your own again. Sally Dee, you are fighting the enchantment! What is it, Sally Dee? What did you see?”

Thrice she said my name, as though by repeating it thusly she could somehow speed my way to dis-enchantment. Or possibly she meant to hypnotize me. I wondered if this was one of the techniques she employed when inducting all her newest supplicants into her closely governed world of fearful make-believe, and what sort of success rate it usually had.

But I knew, as she did not, that Sally Dee was not my name; it was my armor. I strained forward until our foreheads were touching, like I wanted to tell her a secret.

“Caelestis,” I whispered, “there’s no such thing as gentry.”

A full minute we stayed like that, my clammy forehead against her cool one, our eyes almost crossing to keep fixed on each other’s at such close range, before she murmured, “Hmn,” in a vaguely disappointed way, and stepped back from me. She wiped my sweat from her forehead with a handkerchief. Her gaze flicked to the pursuivants. “Pursuivants, I am afraid we have a cynic in our midst. Cynics, Mrs. Dee,” she turned and explained kindly, “always fall the hardest to gentry enchantment, because they do not believe it exists. This…inflexibility reinforces the spell upon them.”

I snorted. “How convenient.”

And it was—quite a serviceable excuse for culling the disbelievers from her herd, isolating them, subjecting them to far harsher treatment than the gullible and compliant—until their wills were broken.

And this, I realized the very next moment, was to be my fate.

“Put her in the Wells. The water should wear away at what enspells her, clear her befuddlement. Work,” the abbess added, her gaze locking once more with mine, the little twinkle in her eyes expressing not mockery but also not anything that might be categorized as compassion either, “is only one of the cures for enchantment, Mrs. Dee. There are others. Pain. Hunger. Remorse. A period of contemplative solitude…”

“How long?” I blurted, alarmed. Even if Gazala Lal and Auntie Lu came after me—even if they brought their large-cannon civil liberties lawyers to bear upon the abbess, and managed to obtain her consent to search the Seafall City Laundries from top to bottom—there was no guarantee they would ever find me, stuffed somewhere at the bottom of a well. The abbess knew it too. Her eyes were still twinkling, like the glimmer of water at the bottom of a deep, dark shaft.

“However long it takes,” she answered with mild surprise.

They were already dragging me away. “Caelestis, damn it!” I shouted, “how long?”

“When next we meet, Mrs. Dee,” the abbess chided me, never even raising her voice, “do please bear in mind that the appropriate form of address is Your Holiness.”

Chapter vi. In Which, in the Dark of the Wells, I See Strange Writing and Learn Terrible Things

I am not so alone as she thinks me. Other than emptying my pockets, the pursuivants did not search my person. Therefore, the notepad and pencil I have kept cached in my underthings remain with me. I have you, Reader (or will have, one day, in the future), for company. I write in the dark, though I cannot read my own words, and wonder if my feet will ever be dry again.

* * *

So many cellars beneath the brickhouse. As many as the rooms above them. More, for these rooms are smaller, cell-like, honeycombed together in an almost lightless warren. Each with its own particular smell. The sweet rot of aging fruits. The musty whiff of withered root vegetables. The fermenting porridge stench of small beer. The gassy miasma of kitchen offal and ash bins. I recall the coal cellar most clearly. The largest of them seemed to go on forever, like the hollow belly of a mountain. That sharp, lustrous shine of anthracite, shimmering! Like gleaming eyes. Like black stars. As we walked, we seemed to be making our way to the oldest part of the cellars. The corridors grew narrower, damper, darker, the ceilings lower, the rooms smaller, the masonry crumbling. I lost all sense of time, direction, distance. How long did we walk? Miles. Ages. Till we came to the bricked-in room with the bars. The room with the round hole at the center of the floor, dropping down into darkness. My home, for the present.

* * *

I have been thinking. There is a modern well and pump in both the men’s and women’s yards. This particular well, then, must have belonged to the old structure, from before the brickhouse was built. It is an old cistern, now dry. Dry-ish. There is about a foot and a half of standing water. Perhaps at one point the cistern was set a little ways away from the house it served, before this angular, efficient, brick monstrosity reached out and swallowed it. There is no light here. I write by feel alone. I keep my place on the page with my finger. I hold my pencil to my nose, inhale the familiar scent of red cedar and graphite. I might be anywhere in the world, inhaling this same scent: words before they are written. I might be, but I am here.

* * *

Today, or whenever it is—tonight, I should say, since down here it is always night (and isn’t that what they say about the world of goblins: that it is always night and never day? That the gentry exist in a state of perpetual twilight, but the koboldkin are midnight creatures, and in the World Beneath the World Beneath there is no moon or stars, only an enormous metal sphere that is the heart of all Three Worlds, that hangs suspended at the center of a maze of bones, a labyrinth filled with creatures so foul that whenever any one of them encounters another, they must devour each other on sight or perish of fear. Bsut what was I saying?)…tonight, I am just able to see my own hand as it writes, as well as the page it writes upon, two blurs only just distinguishable from each other in this otherwise lack. Still, an improvement! My eyes are adjusting! I cannot make out any of my words, though.