From the pages of Dark Breakers

Longergreen

C. S. E. Cooney

Illustration by Brett Massé

for Lea Grover

No one remembers how beautiful they are. Look away a moment, you forget. Look back, it’s like being fire-hosed with a hundred fifty gallons of gorgeous a minute.

The gentry are like how food tastes when you’re high; every bite freshly astonishing. You eat until you’re full, until you’re gorged, because you can’t remember the last bite, because the next bite is also your first. And the first is best. And again. And again.

The gentry are deadly in excess. And it’s only ever always excess with them.

But, no. No, looking at the gentry isn’t like being high. The gentry are the high. Their whole realm—the Valwode, the Veil Between Worlds—is itself one long trip. Or a short trip. Then a fall.

Linger too long, it means death or oblivion to mortals like us, unless we can somehow become more gentry than mortal, and that’s a thing that takes outside aid. We can’t do it on our own.

Here among the sleak oaks, I found my outside aid.

“Ana,” said the Gentry Sovereign in its gentle voice. “I have missed you so much.”

* * *

It was seven and a half hours from Seafall to the Cloudlands, a mountain range that sawtoothed through several states of Southern Leressa. A nice drive but a long one, with messy stretches. Traffic in Seafall. Two busy bridges (both under construction) to get off the Federation Islands. Stop-and-go on the ILD (the “Interstate That Never Sleeps”) before it opened up beautifully out in the boonies. And then, of course, on the outskirts of Amandale, I ran into rush hour.

But after that, scenic country roads. Fewer potholes than I recalled. More titanwood trees than I was expecting, given the gentry moth blight two years ago. Must’ve been some miraculous comeback, or else it wasn’t as dire as all the arborists were foretelling in the mainland journals. Gideon used to read those rags obsessively as well as the local newspapers. Me, I preferred novels. But he always liked non-fiction better than fiction, and in later years, favored journalism over history books.

“It is history,” he told me, “for people who aren’t born yet.”

He still read my fiction. Not, I think, just out of a sense of loverly duty either. He told me once, “Your truths require the medium of phantasmagoria for total absorption. But you have been as much a journalist as Sal Dimaguiba, in your way.”

“In my way?”

“Kind of.” He grinned. “In your inimitable way, Ana.”

“Thanks, lover,” I growled, giving him the three-fingered salut.

At the time, Gideon knew as few did that my most outrageous plots and preposterous characters were pretty much straight reportage. But it was only later, when the Tumble occurred, that scholars realized it too. (There was a fancy word for the Tumble—Ymbglidegold—but it was so archaic no one ever used it.)

Tumble Summer was the year the boundaries evanesced, and “the walls between worlds fell down.” For the first time in centuries, the denizens of Athe, Valwode, and Bana the Bone Kingdom—the Three Worlds of our so-called “three-petaled World Flower”—came into regular contact with each other, and all the old stories and songs long since dismissed as “gentry tales,” “goblinygabble,” and “veil rhymes” were dragged out, dusted off, and re-examined as urtexts for an integrated way of life we’d all forgotten.

My own books—already decades out of fashion—should have been superfluous at that point. Why read musty old novels of chance human encounters with gentry and koboldkin when it was so easy to saunter up to one of the newly boundary-less locales—Breaker House in Seafall, or White Raven Island, or certain neighborhoods in Drowned Lirhu—and interview a downworldly creature for yourself? Suddenly, our world of Athe was saturated with a new flavor of celebrity: non-humans. Our magazines, talk shows, radio shows, and graduate students with dissertations to write all welcomed exclusives with our new/old neighbors. But when the lamps of academe lit upon the notion that I’d been writing fact as fiction for years before the cataclysmic events of Tumble Summer, my old books gained new popularity. They were relabeled “mythoir” and shelved in with the classics. Not such a terrible thing to witness in my lifetime.

Gideon said my newfound fame made Ymbglidegold worth it to him—for whom otherwise it was unmitigated torment. He kept all my press clippings in an album. I’d brought that with me on my journey as well.

When I hit the foothills-portion of my road trip, the land began to change and rise: the marches of the Cloudlands. The asphalt gave way to gravel, farmland gave way to hardier orchards—peaches and plums, mostly—and the occasional vineyard. These graduated to mountainous cow pastures, where great brown bovines and their friskier calves stood too near the road and watched me drive past. Their interest surprised me, ranging as it did from mild to outright curiosity. I thought the domestication process had bred all that out long ago.

Gideon rode with me, in the small urn he had carved himself.

“Razor-sharp tools and a light touch” was his rule with purpleheart. He liked working with difficult wood. “Purpleheart’s hard stuff”—he’d say, glancing up, smiling just a little—“in more ways than one.”

Burns easily. Resists decay. Over time, it changes colors: from true violet to deepest brown. He had taken his time with it. He said it would age like my grief.

Or maybe I’d said that. He wasn’t talking much last year. Maybe he just looked, and I filled in the rest.

The cancer had eaten his throat by the end, taking voice and appetite with it. But age and practice had also quieted him, mellowing his bitterest edges. It wasn’t that we’d said all we had to say after being lovers for sixty-odd years. Quite the opposite. Only, Gideon could communicate multitudes with a glance, a hand on the back of my head, a nudge of the foot. If I burst out laughing in the middle of an otherwise silent afternoon, all he’d have to do was cast a quick, bright look around for context, and he’d see the joke right away. Sometimes it was a cartoon in the funnies (we liked a strip called Carlotta the Clown). Or a cat thing (they adored my typewriter, but only when I happened to be using it). Or something spotted out the window (a hummingbird dive-bombing the pregnant squirrel who’d gotten into the feeder again and was bottoms-upping the nectar like it was grog and she a very furry sailor). It was usually small, common. The sort of thing that, later, turns sharp, twists like a knife.

Gideon was never one to laugh much, but oh! How he smiled. A smile that transformed his wintry landscape like a crocus bursting up out of the snow.

Sometimes when he smiled, I feared for him. Historically, the gentry only stole the youthful and the beautiful—or the spectacularly talented. Gideon had learned that firsthand as a boy. But even as an old man, even stooped and silenced and cancer-riddled, Gideon had a smile that could lure a gentry sorceress out of her perpetual twilight, and spur her to snatch him up, and bear him back to her white tower in a black thorn wood, and keep him forever by her side. I used to tease him that only his hair protected him, now that I was too old to go diving downworld after him. His hair had never gone completely white, just gray—a rippling gray like corrugated iron.

Iron, of course, still repelled the gentry somewhat. Not like it used to before the Tumble. But somewhat.

I’d been trimming Gideon’s hair since our first year together. He always wanted me to cut it all off just as his curls began to show. He’d tried growing them out a few times for my sake, because I was wild about them, but whenever his hair reached a certain length he couldn’t stop playing with it. That, he did not like. Anything Gideon couldn’t stop himself from doing made him want to unzip his own skin. Pulling and releasing his curly hair. Smoking. Drinking. Snapping people’s noses off. All his old habits. As soon as he recognized some compulsive behavior as having a hold on him, he’d excise it from himself as mercilessly as a surgeon.

But last year, he didn’t mind his hair so much. And it was I who couldn’t help running my hands through it, kissing the curls I twined about my fingertips. He’d looked up at me with those sharp black eyes beaming fiercely, and I knew he loved me, resented leaving me, but he was just so tired.

He was awake when he died, his hand knotted in mine. He’d bring it to his lips from time to time, dreamily. The last time, he pressed my hand to his face, and sighed.

It was good. If a death can be good. I can say that now.

* * *

Among the sleak oaks, the Gentry Sovereign reached out its long pale arm and touched my hair.

No shock or disappointment shone in its black eyes, only tenderness—even though my hair was no longer thick, no longer red, no longer the anarchic half-frizz, half-frat party it once had been. Alban Idris used to love brushing out my hair, silently, ardently, burying its face in the tangles as though warming itself at a hearth. But now, all that bonfire abundance was scythed to a fine white stubble, standing on end under that huge, cool palm.

I hadn’t shorn my hair for grief. That had happened well before Gideon got sick. For all I was still fairly fit and sturdy for my age, and more active than some, my long hair seemed to belong to another Ana. I had changed, in surface ways and deep. Who now could recognize in this old, grieving Ana the fiery, young Analise Field of yore—Alban Idris’s first friend? How could it see me and know me and still look at me that way?

And yet, it did.

The Gentry Sovereign itself had not changed. It, like all the gentry of the Valwode over whom it ruled, was forever beautiful. Infinite loveliness in its lines and curves. Eternally unchangeable and simultaneously starkly astonishing.

I almost could not bear to look at it. There was that in its face that reminded me so of Gideon, for Alban Idris was the work of Gideon’s hands: the last statue he had ever made in the mortal world of Athe, and one whom he would have destroyed, if I hadn’t intervened.

I was crying again.

The Gentry Sovereign’s hand was stroking my hair in such a way—such a way!—as I remembered from a lifetime ago.

Then it withdrew.

Just for a moment. Just to catch one of my tears on the iridescent nail of its index finger. Gracefully, abashedly, Alban Idris examined my tear, and then sighed deeply, blowing out a gentle breath upon it.

I watched, baffled. (Alban Idris did not, in general, need to breathe.) Now, instead of a tear, a glistering jewel sparked on the tip of its finger. A diamond drop, or something more precious.

“May I?” it asked me, so earnestly that even though I didn’t know what it wanted, I couldn’t think of a reason to say no. So I nodded.

“Thank you, Ana,” said Alban Idris, and hung my vitrified tear from a low-hanging tine of its antler crown.

I couldn’t help asking, “What’s that for?”

“I like to have the things of you nearby.”

I noticed then, snared amongst its tanglewood of antlers, various elements from my life: a page torn from my first book, Seafall Rising; a slim red braid, with bits of ragged ribbons tying up both ends; a half-empty ink bottle, the gold-marbled blue lid of a long-lost fountain pen.

“Oh, my dear one.” The softness of more than just age was transforming my face. I moved to cup that long, planed cheek with the palm of my hand—even if it meant bringing my blue-bulging veins, my sunspots, my wrinkles close to its perpetually perfect face.

The Gentry Sovereign’s big black eyes fluttered shut at my touch. It breathed out, then in again, then out, with all the land-large relief of mudcrack after a summer storm. It opened its arms to me, and I folded myself into them.

There. Cool petrichor. Quiet calm. Like entering a museum after doing pitched battle with pedestrian foot traffic and the bright battering ram of busy city streets. Just there.

When Alban Idris moved, lifting me and carrying me across the glade, it was as subtle as a cool evening breeze stirring a leaf to flight. No surprise, no panic. Nothing but ease as it settled us into the moss, me in its lap, it with its back against a sleak oak. Cradle comfort, seat of silk, not an ache, not a creak. It all happened so softly I scarcely noticed it, only startling upright when I realized I had been, at some point, disburdened of my backpack. Gideon’s urn, however, was still with me. A weight in my lap. As nestled into me as I was into Alban Idris. Nesting dolls, the three of us.

“This is good,” said Alban Idris, in a tone of peace and satisfaction.

I agreed with a soft grunt.

“You have not come to this glade for so long, Ana.”

I turned my head to look into its eyes. “How did you know I used to come here?”

When it became apparent that Alban Idris would not answer, I asked, “Did you…did you ever see Gideon here?”

I stroked the carven urn of purpleheart wood. It felt warmer against my skin than did Alban Idris. Warmer, but less alive.

“A few times. When you came here together on picnics.” Alban Idris paused. “A few times, alone. He walked here when you were visiting that house yonder.”

It waved, indicating the old hunting lodge nestled just out of sight on the other side of the oak mott. The lodge used to belong to millionaire tycoon H. H. Mannering. After he died, the lodge functioned as a historic museum owned by the state and run by docents. Summer camp kids went there on field trips to learn how to bake measure-cakes over an open hearth, and track gray and red foxes through the woods. Tourists posed for photo ops: flexing near a replica of the fancy-finish, semi-automatic Alderwood rifle that H. H. Mannering had favored, or squatting over the millionaire’s second favorite chamber pot. (His first favorite chamberpot was tucked discreetly away in a handsome marquetry commode cabinet, with walnut inlay and marble accents, surrounded by velvet ropes forbidding trespass.) I’d visited the museum several times over the years until the state shut its doors due to budget cuts.

“The last time I saw him,” Alban Idris recalled, “you went into the house alone, with your camera. He boosted you through a broken window.”

I blushed. After the lodge museum closed, I’d regretted never taking photos of the interior layout, which I wanted for a book I was writing, wherein the lodge featured as my central location. So Gideon had helped me sneak in.

“Five other times before that, you were visiting the house with friends. But the first time, I remember, you brought a young one with you—whose mother was Nyx the Nightwalker, Queen Emeritus. I could smell the Valwode on her.”

“Neffis. Her name is Neffis Howell.”

“Neffis Howell,” the Gentry Sovereign repeated, its voice like a cave behind a waterfall. “She was a child scarcely fledged.”

“Well, she’s all grown up now, and then some. A retired accountant! But if we brought her up here, she’d have to have been, oh, just about eight or nine at the time.”

Strange how those distant memories seemed more recent than last week. Neffis, gangly, nervy, equally embarrassed by—and curious about—everything. The way she ran away from her parents, appalled by their constant hand-holding and frequent kissing. The way she ran back to them whenever she found something—just anything!—beautiful or odd, and had to show them. Sometimes Gideon and I would take her to special places like the lodge museum, just the three of us, to give her parents some time alone together.

“You always went inside the house, Ana. But he never did.”

I shook my head. “No. Gideon hated the place. His last interest in the Mannerings disappeared the day his cousin Desdemona did. This glade, on the other hand”—I looked around—“he loved it as much as I do.”

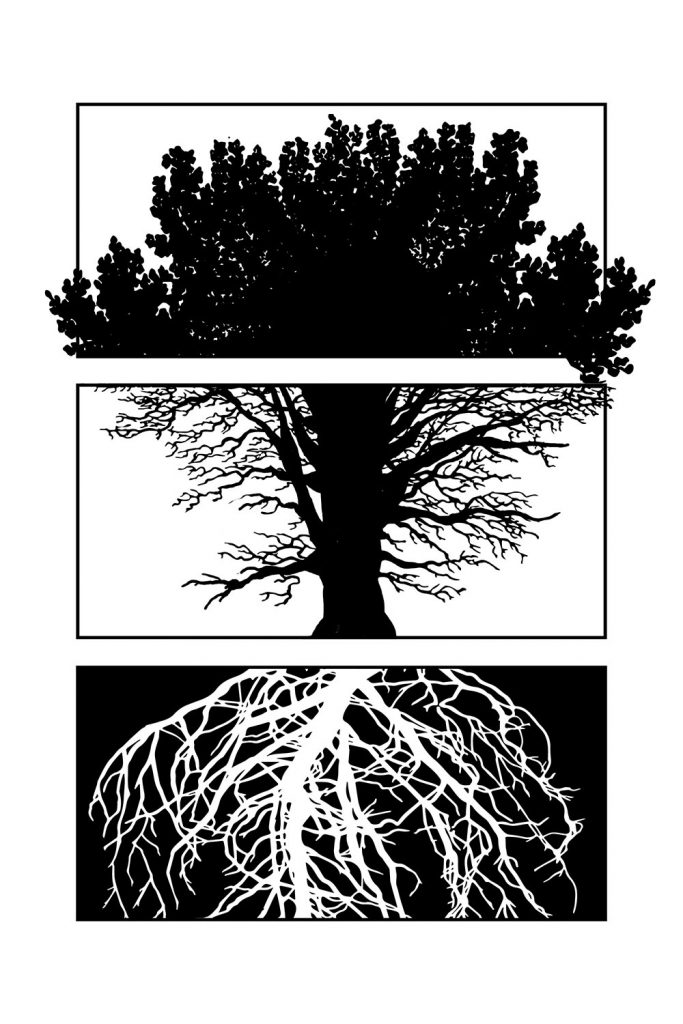

The malachite mott of old white oaks was one of our chief destinations whenever we came to the Cloudlands. It was just a three-mile hike down the mountain from the Howells’ cabin, most of it by gravel roads and well-kept state forest paths. The trees were all Southern Leressan escarpment oaks—the “oak-of-ancients”—or more colloquially, the “sleak oak,” celebrated in song and poetry for being evergreen and all that that implied. I once complained to Gideon that sleak oaks were not so much evergreen as longergreen. They always dropped their leaves just before the new ones pushed through in spring.

“For a fiction writer,” Gideon told me, “you demand inordinate accuracy from bygone botanical taxonomists.”

I told him, “Whatever, Gideon.”

My favorite thing about sleak oaks was not their longevity. It was that, though the trees were tall, though the tops of their crowns might attain seventy or eighty feet, they were yet not as tall as their limbs were long. I always thought of those far-flung, grandma-gnarled, down-sweeping arms as beckoning me into an ever-bountiful embrace.

“This place always reminded me of you, you know,” I told Alban Idris. “My beloved friend.”

“In the Valwode, it is one of my sacred glades,” said the Gentry Sovereign, “for it has always reminded me of you, Ana.”

“I’m so glad,” I said. “I’m so happy, my dear one, that you were thinking of me too, all this time.”

“There is no time that I do not.” It shrugged its sky-breaking shoulders, as if it bore the weight of another world upon them. “What is time to the gentry?”

Suddenly overwhelmed, I leaned back in my friend’s strong embrace, and overlaid its long, corded arms with mine. Together, we stretched our arms wide, as if embracing every tree in the grove. I laughed—and though Alban Idris did not laugh with me, it had a way of smiling with every surface of its stone-like skin: a sun-flush, a glistening.

“Look,” it whispered, right against my ear, and then breathed lightly upon my eyelids.

Almost at once, the world began to shimmer. The trees grew trees within trees. A phantom forest sprang up all around me, each overlapping and translucent tree occupying the same space as the trees of my world, but never the exact same shape. I saw, not just the sleak oaks of Athe, but the luminous, abalone-barked, tree-shaped shells of the Valwode. Cloisterwights inhabited these trees like hermit crabs: slow-moving, strangely arboreal in aspect—but as changeable, as generous, as vicious as any of the gentry. With Alban Idris’s breath crystalizing upon my eyes, I peered through the Valwode trees and deeper, right into the trees of Bana—the World Beneath the World Beneath—where they were pillars of glowing bone, their skeletal branches festooned with thread-of-silver floss, their trunks mottled with moss-colored emeralds.

This glade, apparently, was one of the so-called “exceptions.” A boundary-less place.

We have words for what happened during Tumble Summer, when the Three Worlds came undivided of each other. We say “the boundaries crumbled,” or “the walls wisped away,” or “the borders disintegrated.” But it wasn’t like that, not really. There were still divisions between our worlds, but they were natural ones, like rivers or mountain ranges or canyons. It was only the artificial walls that had melted, the ones made centuries ago by a magical alliance to stop a long and bitter war between our worlds.

But—and this was important—even after Ymbglidegold, our worlds were still separate from each other.

Mostly. With exceptions.

The oak mott, it seemed, was one of these exceptions. And Gideon must have sensed it—even if I hadn’t.

“Gideon used to take me on surprise picnics,” I remembered aloud. Layer after layer of uncanny trees faded gently from my vision, leaving only oak, only moss. I didn’t know whether I was regretful or relieved. “He’d pack us a lunch and lead me from the cabin on a long ramble, never telling me where we were going. We’d often end up here. Lie on a blanket in the shade. Eat sandwiches. Read to each other.”

“I know,” said Alban Idris.

“But you saw him when he was alone. What was he doing out here?”

“Pacing, mostly. He would move about the glade but did not look up from his feet. Sometimes he pulled a crumpled cigarette from the inner breast pocket of his jacket and contemplated it.”

The Gentry Sovereign had let our arms fall so delicately, I hardly realized we had moved until I found my own hands folded together neatly in my lap. Now Alban Idris’s arms were fast around me, the surface of its skin growing warmer, matching itself to mine. I’d forgotten that little trick.

“Ah, yes,” I said. “Gideon and his secret cigarette.”

“He would look at it, and want it. But he would not smoke it.”

“No,” I said. “He wouldn’t.”

Gideon only fiddled with his old habit whenever he was anxious. When he was remembering his time as a prisoner in the Valwode. When he felt the presence of the Valwode drawing too near to him. He could smell the gentry like a perfume he was allergic to. If the sleak oaks in this glade had ever revealed themselves as more-than-trees; if the moss shone with emeralds and the bark shimmered abalone; if Alban Idris, concealed behind a thrice-enfolded trunk, was watching its maker warily, eyes as black as a tear in the worlds, Gideon would have felt it. My hands stiffened around the urn like claws.

“You saw him. Did Gideon ever see you?”

“I did not reveal myself to him,” the Gentry Sovereign replied. “But I think he knew I was watching.”

“Did you…did he ever speak? To you?”

“We never spoke.”

I hefted the urn higher, clutched it hard to my chest. “I wish he’d talked to you. I wish he’d tried.”

The Gentry Sovereign shifted beneath me, tectonically. “Ana. Perhaps he sensed I was not ready. Perhaps he knew I was not here for him.”

How closely it was matching its heat to mine, its heart to mine. How it set the buzzing in its breast to mimic my own heartbeat. And how, when I was silent for too long, its whole body began to tremble.

“Alban Idris, my dear one,” I asked, and my voice was trembling too, “what do you want of me?”

* * *

Tired as I was after my long trip from Seafall to the Cloudlands, the first thing I did upon arrival was empty everything out of my car. It was twilight when I rolled up to the cabin’s driveway, the air a luminous lividity. Katydids and crickets played their stridulating symphonies. Clouds clustered like bruised violets over the mountain peaks. Elsewhere, the sky was a bowl of clear cobalt glass overbrimming with stars.

It was a push to make those several trips from trunk to front porch, from front porch to front room, and then, once inside, to put everything away in its proper place. But I did not like to leave an untidy trail of needful things undone. Mornings were unpredictable, my body growing strange to me. Many times I’d come back to a fuller awareness of myself in bed, only to realize I’d lain awake all night, staring at nothing, my thoughts like a radio left on in another room, tuned to no channel. While I was functioning, I had to plan for these moments of incoherence, so that when the storm of grief came on, I’d be better able to weather it.

Because the grief would come.

Gideon’s urn I first placed on the mantel over the fireplace. But that seemed too far away. So I brought him with me from room to room as I turned on all the lights and plugged in the several electric heaters scattered through the cabin. There was a big storage heater for the main room, built like a bastion, wonderful at releasing the warmth stored in its bricks all day long. But it needed to be charged overnight. Several smaller, more modern, portable heaters squatted in the corners of bedroom and bathroom and kitchen, and in a little while, my breath no longer preceded me as I moved through the cabin.

I didn’t light the fire. Gideon had always been fire-keeper in our house.

“Gideon of the Hearth,” I called him, while Elliot, sprawled on the couch (that very couch, with its scratchy orange cushions stiff as boar bristles, and its fold-out bed so uncomfortable that most guests preferred the floor) whispered loudly, “Pyromaniac!” and Gideon, glint-eyed, wielded a lit brand in his direction.

Then Nyx, striding in barefoot through the cabin’s open front door would laugh and exclaim, “Children!” in her voice like a love-rasped whisper. “Are we playing with fire tonight?” and Elliot, springing up for a kiss, saying gladly, “Every time I touch you.”

Only when they were fully occupied with each other, not watching us, would Gideon cast his brand into the flames and turn to me, where I was lounging bellydown on the hearth mat, and draw me hard against him with the almost palpable click of two pieces fitting together.

Oh.

It had happened again.

I blinked. I was kneeling in front of the empty fireplace. I did not know how long I had been there. Staring. That small heap of ash in the hearth. We must have forgotten to sweep it up the last time we were here. Two years ago. The remnants of Gideon’s last fire.

My knees ached. My hands were filthy.

But this, I told myself, was what I’d come here to do. To kneel on the cold floor, to remember and remember, until my stiff body reminded me that even at age twenty it would not have gladly endured such abuse, and now, as I was heading into the deep shade of my late eighties, it doubted it would do me the honor of ever rising again.

But bladders are great motivators. And I had a cane at hand, for whenever I needed one. While one inevitably has one’s little emergencies and accidents, I wasn’t ready to relinquish all control over such matters.

Not yet anyway.

* * *

The Gentry Sovereign did not answer me directly. Instead, he indicated the urn.

“He was always like a window, smoked over. A floating window that moved as he did, but always apparent to me. Sunlight from a different world fell through him onto my face, but dimly. Sometimes, if I drew near enough to his window and dared press my cheek against the glass, I could see your face through him. It was a way to be near you. That was all I ever wanted.”

“You wanted to watch me grow old, Alban Idris?”

“To watch you grow,” it said, with a longing so raw that my eyes spilled tears again. “Things do not, you know, as a rule, in the Valwode. Not naturally. Everything that moves or changes, moves and changes because we who rule there will it. We dream the change. But how can we dream change if we ourselves never do? And so, I look to you. To learn from you. As I have always done. And—”

But here it hesitated, and looked almost ashamed.

“And?” I prompted.

“Ana,” it said, “I was waiting. I was waiting for you. Hoping. Surely he would die before you. Surely he would have grace enough for that. Even he.”

“Well,” I said, with a laugh that was not one, “he did.”

“I…I have regretted my desire ever since. In the Valwode, where I wear the Antler Crown, my desire is strong enough to pull the tides to me, to reorder mountain ranges, to uproot the wood and make it walk. But, no matter what I wished for, or how hard I wished it, my desire could not have affected any change on Athe. Ana, I did not bring his cancer; I swear it. But if I could have—”

“No,” I interrupted it. “No. You wouldn’t have.”

“I am not so sure.”

“No.”

The Gentry Sovereign stirred restlessly. “It is so…strange…now, without him. My window into Athe went dark. It used to be, no matter where I was in the Valwode, I could sense wherever he was on the other side of the wall. A simple matter: just turn toward the heat, the light. I knew his movements, always. When came the Ymbglidegold, it grew even easier. There are places now, where the Veil Between Worlds is so translucent, if you stand still long enough, quietly enough, you can see the stars of Athe. Likewise, if you stand at wells, at caves, at edges, you can peer right down into Bana the Bone Kingdom. While he lived, I would sometimes leave Dark Breakers in the hands of my queens, go wandering after his light. I knew that, wherever he went, there you would be too.”

“Wait!” I put up both hands to pause its confession.

Obediently, instantly, the Gentry Sovereign stopped speaking.

“Go back, go back!” I said. “Your queens?” Excited as a schoolgirl sharing confidences at her first overnight slumber party, I clambered around on its lap till I was sitting face to marble face with it. “Alban Idris! Are you married? When did this happen?”

“Two years shy of six decades ago,” it answered promptly. “As you mortals reckon time.”

“And you’re just telling me now? Who’s the lucky gentry? Or, rather—who are the lucky gentry? You did say queens, plural, didn’t you?”

Its pale lips curled, almost coyly. “You even know one of them, Ana—or, at least, you used to, in your youth. I had hoped to re-introduce her to you one day. To introduce you to both of my queens, as the first love of my life.”

I shied away from addressing that directly; it was too close to the subject we had both been dancing around.

“And…do they love you too?” My darling, my beloved friend! They had better love it, I thought, those queens who shared the Valwode’s silver-razor throne! The thought of Alban Idris, trapped forever in the twilight, bent under the weight of its own power, and starving for any tenderness cut me to the quick.

But it answered at once, saying, “Yes,” in a firm, sure voice. “We all love each other very much—though we find we are infinite mysteries to each other. It is not easy, sometimes—most of the time—to communicate. Or agree. Or compromise. But”—and here it smiled again, not coy at all now, but fond and warm and rueful—“my queens teach me so much, and tease me constantly, and try to tell me jokes, and teach me how to dream, and shower me with more affection than I deserve.”

I clucked my tongue. “You deserve all of it. All of it!”

“I do not know, Ana. Before they came”—Alban Idris shuddered—“it was horrible. I ruled the Valwode all alone—and, Ana, I did not know how! It was dying all around me. But since we wed—to save the Valwode from collapse—we have managed to stabilize the dream, to build it up again, and break down barriers wherever we find them. It was the three of us, you know,” it confided to me shyly, “who ushered in the Ymbglidegold.”

A blush of pride crept into its cheeks, like marble slowly warming to a rosy pink quartz. Oh, it had changed our worlds, this once-timorous creation of Gideon’s. It had changed all our worlds for the better.

“I’m so glad,” I said again, feeling the phrase insufficient, but meaning it. I was glad that Alban Idris was no longer alone, no longer afraid, no longer so bewildered. It had found partners who loved it and work that gave purpose to its eternity. I have had occasion to think, this past year, when there were days that seemed like eternities, that having to endure grief for eternity would be a greater tragedy, even, than death.

Something in my body or perhaps a sound I made, stole the delicate color from the Gentry Sovereign’s face. It laid its hand over mine upon the urn of purpleheart wood.

“His light and heat are gone now. Yet some trace remains. Like the smoke that lingers when a flame is blown out. A particular flame.”

I cradled Gideon close. But I had less a sense of him than even Alban Idris did. I could go nowhere but inside myself to find him, and every time I did, he retreated further, grew dimmer. It wasn’t just Gideon either. My memory for recent events was becoming tangled; tracking conversations required much greater effort than it ever used to; my powers of concentration were slipping from my grasp.

I knew what was happening, why my memories only grew clear and sharp the further back I reached. I’d seen it happen enough times to peers and family members. But oh, I begrudged it. I wanted to keep it all, right up to the end. I was greedy to recollect everything, to hold it sharp and vivid for as long as I had life left in me. Outrageous, outrageous that I should forget even a minute, even a second, of my own dear life, and all those whom I have dearly loved! Especially Gideon. Especially him.

Rather than being taken aback by my innermost ferocious thoughts, the Gentry Sovereign seemed instead to take courage, and finally dared ask the question foremost in its mind.

“You are the flame I wish to keep burning. Ana. Will you not come back to the Valwode with me?”

* * *

My third morning at the Howell’s cabin (it belonged to Neffis now that Elliot and Nixie were gone, but she hated it; the memories hurt her too much, so she’d given the keys into Gideon’s and my keeping), I went for a walk in the fog.

Gideon’s urn was with me, in my backpack, along with a bottle of water, some trail mix in a beeswax bag, and a first aid kit. His voice was in my head, too, asking me if it was wise to be walking alone in such a wild place—where bears and bobcats were not uncommon, where rattlesnakes sprawled like idealized odalisques on every sun-warmed rock, and drunken hunters might mistake me for a deer.

That same voice had tried to stop me from going on this trip in the first place. It had warned that the roads were lately growing too unfamiliar, and my driving increasingly tentative, and my speeds dangerously cautious.

Only when I’d snapped, “This is probably my last trip, Gideon! You know and I know it. But I have to do this. You wanted your ash in that glade. I’m getting it there if it’s the last thing I do!” did the voice grow quiet again.

And now, after three days of what one might call a sulky silence, it had started up again.

“Look,” I told Gideon’s urn—well, myself—firmly, “I’ll keep to the road. I’ll follow the path markers to the lodge and not go off into the trees. I’ll watch for scat.”

“You left your cane behind,” grumbled the Gideon in my head. “You should pick up a stick. A stout one. Taller than you. You’re not as colossal as you imagine yourself, Miss Analise Field, Authoress.”

“You,” I told him, “talk a lot more now that you’re dead.”

To which, unsurprisingly, Gideon had no response.

Godsdamnit. I’d made myself cry again. But I did as he suggested, and sought out a stick at the edges of the misty road.

Mornings were often foggy in the Cloudlands. It was one of my deep pleasures to sit on the front porch of the cabin and let my mind drift into those shifting grays. Stories and poems came to me at those moments, or—as I grew older—memories: unbidden, ungraspable when reached for, but appearing like a gift out of the very fog itself.

When I was a child, living on a farm in Feisty Wold—long, long before the Tumble—I used to imagine foggy roads as places where the boundaries between our supposed Three Worlds were thinnest. I thought if I just walked long enough into those shrouding vapors, I might accidentally discover the Valwode where the gentry dwelled. They would welcome me (of course), and I would live among them, forever young, in an eternal dream. Or, perhaps, wandering through the mists, I’d accidentally stumble into a hole, and find myself all the way down at the root of the World Flower—in Bana the Bone Kingdom—among the koboldkin. There, I would do commerce with the goblins, exchange my rucksack stuffed with old junk: buttons, chewing gum, fishing line, safety pins (considered by the goblins treasures beyond price) for things they considered trash: precious ore, wishes, rare gems, secrets.

I’ve always loved the fog. Gideon, on the other hand, found it oppressive. He slept longer on misty mornings, only truly rousing himself after the sun burnt all the gloom away.

That morning, I reveled in the cool mystery of my foggy road for as long as it lasted. My pace was no more than dawdling though, and soon enough the autumn sun, doing its last, blazing imitation of summer, replaced my landscape of clouds with clouds of gnats that cheerfully mobbed my slow progress with all the impertinence of paparazzi.

A half-mile up the mountain from the Howell’s cabin, the road ran out into cow pastures and private property, patrolled by large dogs who became a little too excited at the appearance of strangers. A half-mile downhill, the road dipped precipitously, and the descent became much steeper. That three-mile hike down to the museum lodge, once so pleasurable and easy, would doubtless tucker me out on my return. It might take me well into the evening to climb all the way back uphill again. Three miles down, ten miles up, as they say.

But I was fixed on my destination, knees or no knees, heat and humidity notwithstanding. I’d promised Gideon. The real Gideon, not the grumbling voice in my head. He’d have done as much for me, and more, if I’d asked him.

As soon as I turned off the road and into the trees, following those old signs indicating Mannering Hunting Lodge, my sweat cooled and I grew more comfortable. The path was mostly level, kept tidy by the forest rangers, and clearly marked. I passed the lodge with hardly a glance at it, making my way further into the oak mott beyond. The canopy of sleak oak leaves hung windless and uncreaking, on one side glossy green like patent leather, on the other a lamb’s wool-gray. My gnatty companions fled the dense darkness, where the light-starved inner limbs of the oak trees were illuminated only by ghostly clumps of epiphytic ball moss. Black acorns crunched underfoot like a carpet of anthracite.

Out under the sun I had been solid enough. Here, I began to melt and lose my edges. My body slumped like wax.

At first it felt like relief, but that relief was short-lived, existing only long enough to empty me out, lay me flat upon the mossy ground, where the grief rushed over me like a towering wave.

This was the place Gideon’s last wishes had brought me. Not to the Cloudlands or even the Howell’s cabin, but to this green darkness, where even noon took on the aspect of twilight. It was like the Valwode that way.

How long I lay there, I didn’t know. I didn’t even know whether I was asleep or awake, if I had fainted from the heat and exertion, or worse, suffered some catastrophic stroke. All I knew was this drowning grief at journey’s end, leaving me airless, crushed.

And then, one of the sleak oaks opened before me.

This tree was not the tallest, not the thickest in the mott. But it was the one with the longest arms, like an embrace that had been waiting to hold me. The rough trunk split as if axe-smote from within, and the bark parted like brown velvet curtains, and out stepped a blue-veined giant of palest marble. Its eyes were tarry stars, wet-bright, deep black. From the stone-pale pedicles on its brow, there grew a crown of woven antlers dense as a thorn bush. A length of blue velvet wrapped its body, its glowing folds embroidered in tiny red rosebuds, deep green ivy, golden oak leaves, silver stars.

I looked up into the solemn, hopeful face of my old friend. My dear friend. That face that had, from the first time I beheld it, the power to hail the breath from my body, it was so beautiful. That face I had always loved, with the same force and fervor I’d felt for Gideon. And that was when I knew why Gideon had sent me here—of all places on Athe.

“Hello, Alban Idris,” I said.

* * *

Driving away from the Cloudlands seemed a shorter journey than driving into them had been. Road trips, in that way, are the opposite of a hike down a mountain and then back up it, a day ending in a sun-stunned sleep, a confused and clammy wakening, a famishment. Driving home, I felt more comfortable, more sure of the road and my memory of it. I was also six pounds of ash lighter, plus the weight of a purpleheart urn.

The ash we had scattered together, Alban Idris and I. The urn I had given into its keeping—the last thing Gideon’s hands had made.

“It’s almost your sibling,” I said, joking, but also not joking.

“I shall treat it with the tenderness you taught me, Ana.”

The further from the Cloudlands I drove, the more the pressure on my chest eased, the strain of grief and decision and passionate reunion all falling away like forge-scale in vinegar. I was looking forward to home, to the things of home that awaited me.

What awaited me: my three cats: our two old tabbies, fat bundles of rusty purr and patchy fur, and the alert young predator I’d recently rescued from a trash heap out behind the supermarket, who trusted no one—least of all me—but who nonetheless made a clamor at mealtime and who would, if I sat very still with a blanket on my lap, wander into a room nonchalantly and place himself just out of reach near the edge of the blanket, watching everything with the energy of a storm about to burst.

What awaited me: my weekly card night with Sal and Neffis and Neffis’s wife Rennie, though Sal sometimes forgot the rules, and forgot our names to boot, but nevertheless retained that ability to make us (and herself) laugh until our bellies hurt, which was of course more fun than the game itself.

What awaited me: Gentry Moon—now a national, and interworlds, autumn holiday—whereupon my brothers (the three still living that is) and their extended families were all going to descend upon our farmhouse and celebrate with a bonfire night and a potluck feast. My fall garden, too, awaited me: kale, cauliflower, cabbages all wanting to be harvested; pumpkins, turnips, and radishes grown large enough to carve into goblin lanterns. How those traditional, intricate patterns of bones and jewels would cast otherworldly shadows by candlelight. Next year, perhaps, I would not plant a garden, as it was getting hard on my knees. Or perhaps I would purchase a small gardener’s stool, and sit where I used to kneel, and have a garden yet. All of that might be decided in the future, in the warm green spring of Athe, should I live to see it. Should I make it through this winter, as Gideon had not.

Around my neck I wore the acorn of a sleak oak on a bit of twine.

A memento, I could tell anyone who asked. And if they asked me why it rattled so, and why, in the dark, it seemed to gleam, I would tell them a story.

Why, my dear one (I would say, perhaps to one of my great-niephlings as they sat on my lap and played with the acorn), this was given to me by the Gentry Sovereign—one of the Great Triumvirate who rule the Valwode now, and who will rule, perhaps, forevermore. Inside this acorn is captured a single tear that the Gentry Sovereign wept for love of me. Ah, my love, the color of quicksilver it is, all beaded up into a stormy pearl, and hardened like adamant when the Gentry Sovereign breathed up on it. Upon placing the tear inside this oaknut, Alban Idris—for that is its name, love, Alban Idris—told me that as I have its tear now, and as it has mine, we have become windows for each other. If we hold our tears close, and close our eyes, we shall be able to peer into each other’s worlds, and whisper words of love, and assure each other that we are well. And when I am very old—not like now, of course; I’m the veriest babe yet, which makes you but a tadpole!—and ready to breathe my last, it will come to me and offer for a second time what it offered once before. And what I shall say, what I shall say is

C. S. E. Cooney (she/her) is a World Fantasy Award-winning author. Her books include Saint Death’s Daughter, Dark Breakers, Desdemona and the Deep, and Bone Swans: Stories, as well as the poetry collection How to Flirt in Faerieland and Other Wild Rhymes, which includes her Rhysling Award-winning poem “The Sea King’s Second Bride.” In her guise as a voice actor, Cooney has narrated over 120 audiobooks, as well as short fiction for podcasts such as Uncanny Magazine, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, and Podcastle. As the singer/songwriter Brimstone Rhine, she crowdfunded for two EPs: Alecto! Alecto! and The Headless Bride, and produced one album, Corbeau Blanc, Corbeau Noir. Her plays have been performed in several countries, and her short fiction and poetry can be found in many speculative fiction magazines and anthologies, most recently: “A Minnow or Perhaps a Colossal Squid,” in Paula Guran’s Year’s Best Fantasy Volume 1, “Snowed In,” in Bridge To Elsewhere, and “Megaton Comics Proudly Presents: Cap and Mia, Episode One: “Captain Comeback Saves the Day!” in The Sunday Morning Transport—all in collaboration with her husband, writer and game-designer Carlos Hernandez. Forthcoming soon from Outland Entertainment is a table-top roleplaying game co-designed by Cooney and Hernandez called Negocios Infernales. Find her at csecooney.com.

C. S. E. Cooney (she/her) is a World Fantasy Award-winning author. Her books include Saint Death’s Daughter, Dark Breakers, Desdemona and the Deep, and Bone Swans: Stories, as well as the poetry collection How to Flirt in Faerieland and Other Wild Rhymes, which includes her Rhysling Award-winning poem “The Sea King’s Second Bride.” In her guise as a voice actor, Cooney has narrated over 120 audiobooks, as well as short fiction for podcasts such as Uncanny Magazine, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, and Podcastle. As the singer/songwriter Brimstone Rhine, she crowdfunded for two EPs: Alecto! Alecto! and The Headless Bride, and produced one album, Corbeau Blanc, Corbeau Noir. Her plays have been performed in several countries, and her short fiction and poetry can be found in many speculative fiction magazines and anthologies, most recently: “A Minnow or Perhaps a Colossal Squid,” in Paula Guran’s Year’s Best Fantasy Volume 1, “Snowed In,” in Bridge To Elsewhere, and “Megaton Comics Proudly Presents: Cap and Mia, Episode One: “Captain Comeback Saves the Day!” in The Sunday Morning Transport—all in collaboration with her husband, writer and game-designer Carlos Hernandez. Forthcoming soon from Outland Entertainment is a table-top roleplaying game co-designed by Cooney and Hernandez called Negocios Infernales. Find her at csecooney.com.

Purchase from: Hardcover: Barnes & Noble | Amazon | Amazon UK | Amazon CA | Amazon FR | Amazon DE | Amazon AU | Barnes & Noble | BookshopTrade Paperback: Barnes & Noble | Amazon | Amazon UK | Amazon CA | Amazon FR | Amazon DE | Amazon AU | Barnes & Noble | BookshopEbook: Amazon | Amazon UK | Amazon CA | Amazon FR | Amazon DE | Amazon AU | Nook | iBooks | Kobo | Google Play | WeightlessDon’t see it on the shelves at your local store? Ask for it. |

Order direct:

|